Today, June 3rd, marks the birthday of President Jefferson Davis. The birthday of Jefferson Davis is commemorated in several Southern U.S. States: Kentucky (his birth state), Louisiana, Florida, and Tennessee. In the Alabama it is celebrated on the first Monday in June. In Mississippi, where Davis would spend out the last years of his life, the last Monday of May (U.S. Memorial Day) is celebrated as "National Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis's Birthday". In Texas, "Confederate Heroes Day" is celebrated on January 19, the birthday of Robert E. Lee; Jefferson Davis's birthday had been officially celebrated on June 3, but was combined with Lee's birthday in 1973.

The man today best remembered as the only president of the short-lived Confederate States of America actually had a long and somewhat productive political and military life prior to the War Between the States (1861 - 1865).

Jefferson Finus Davis was born in Fairview, Kentucky on Friday, June 3, 1808, the last child of ten of Jane Simpson Cook Davis (1759-1845) of South Carolina and Samuel Emory Davis (1756-1824) of North Carolina. Both of Davis' paternal grandparents had immigrated to North America from the region of Snowdonia in the North of Wales; the rest of his ancestry can be traced to England. Samuel served as a Major in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, along with his two older half-brothers. In 1783, after the war, he married Jane Cook (also born in Christian County, in 1759 to William Cook and his wife Sarah Simpson). Samuel died on Sunday, July 4, 1824, when Jefferson was 16 years old. Jane died on Friday, October 3, 1845.

Young Jefferson Davis and his family moved to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana in 1811, and later to Wilkinson County, Mississippi. In 1813 Davis began his education at the Wilkinson Academy, near the family cotton plantation in the small town of Woodville. Three of his older brothers would serve in the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

Two years later in 1815 Davis returned to Kentucky and entered the Roman Catholic School of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory in Springfield. At the time, he was the only Protestant student at the school. Davis then went on to Jefferson College at Washington, Mississippi, in 1818, and then to Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1821. Davis then attended and graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1828.

During his first military career, Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (current-day State of Wisconsin). There he served with the infantry until 1833 when he transferred to the dragoons. His commanding officer was future U.S. President Zachary Taylor. Davis served during the latter part of the Black Hawk War (April 6 - August 27, 1832).

On Monday, August 27, 1832, Chief Black Hawk and other Native American leaders surrendered to then Lieutenant Jefferson Davis and Zachary Taylor after hiding on an unnamed island in the Mississippi River. Colonel Taylor assigned him to escort Black Hawk to prison. Davis made an effort to shield Black Hawk from curiosity seekers, and the chief noted in his autobiography that Davis treated him "with much kindness" and showed empathy for the leader's situation as a prisoner.

Three years later, Davis resigned his commission on Monday, April 20, 1835 in order to marry his commander's daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor, on June 20th of the same year in Louisville, Kentucky. Sarah died at the age of 21 on Tuesday, September 15, 1835, after three months of marriage after both her and Jefferson contracted malaria while staying with Sarah's sister, Anne at her home in Louisiana. Davis would recover from the malaria, though he would grieve for his first wife for years afterwards. Later after a trip to Havana, Cuba, he returned to Mississippi to become a planter.

In 1840, Davis first became involved in politics when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg, Mississippi and, to his surprise, was chosen as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson, Mississippi. In 1842, he attended the Democratic convention. In 1843, became a Democratic candidate for the State House of Representatives from the Warren County-Vicksburg district, an election he lost at the time. Davis was selected as one of six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election and campaigned effectively throughout Mississippi for the Democratic candidate James K. Polk.

In was also in 1844 that Davis met 18 year old Varina Anne Banks Howell, (1826-1906) whom his brother Joseph had invited for the Christmas season at Hurricane Plantation. She was a granddaughter of New Jersey Governor Richard Howell; her mother's family was from the South and included successful Scots-Irish planters. Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old widower Davis had asked Varina to marry him, and they became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics. The two were married on Wednesday, February 26, 1845.

The man today best remembered as the only president of the short-lived Confederate States of America actually had a long and somewhat productive political and military life prior to the War Between the States (1861 - 1865).

Jefferson Finus Davis was born in Fairview, Kentucky on Friday, June 3, 1808, the last child of ten of Jane Simpson Cook Davis (1759-1845) of South Carolina and Samuel Emory Davis (1756-1824) of North Carolina. Both of Davis' paternal grandparents had immigrated to North America from the region of Snowdonia in the North of Wales; the rest of his ancestry can be traced to England. Samuel served as a Major in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, along with his two older half-brothers. In 1783, after the war, he married Jane Cook (also born in Christian County, in 1759 to William Cook and his wife Sarah Simpson). Samuel died on Sunday, July 4, 1824, when Jefferson was 16 years old. Jane died on Friday, October 3, 1845.

Young Jefferson Davis and his family moved to St. Mary Parish, Louisiana in 1811, and later to Wilkinson County, Mississippi. In 1813 Davis began his education at the Wilkinson Academy, near the family cotton plantation in the small town of Woodville. Three of his older brothers would serve in the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

Two years later in 1815 Davis returned to Kentucky and entered the Roman Catholic School of Saint Thomas at St. Rose Priory in Springfield. At the time, he was the only Protestant student at the school. Davis then went on to Jefferson College at Washington, Mississippi, in 1818, and then to Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1821. Davis then attended and graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1828.

During his first military career, Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chien, Michigan Territory (current-day State of Wisconsin). There he served with the infantry until 1833 when he transferred to the dragoons. His commanding officer was future U.S. President Zachary Taylor. Davis served during the latter part of the Black Hawk War (April 6 - August 27, 1832).

On Monday, August 27, 1832, Chief Black Hawk and other Native American leaders surrendered to then Lieutenant Jefferson Davis and Zachary Taylor after hiding on an unnamed island in the Mississippi River. Colonel Taylor assigned him to escort Black Hawk to prison. Davis made an effort to shield Black Hawk from curiosity seekers, and the chief noted in his autobiography that Davis treated him "with much kindness" and showed empathy for the leader's situation as a prisoner.

Three years later, Davis resigned his commission on Monday, April 20, 1835 in order to marry his commander's daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor, on June 20th of the same year in Louisville, Kentucky. Sarah died at the age of 21 on Tuesday, September 15, 1835, after three months of marriage after both her and Jefferson contracted malaria while staying with Sarah's sister, Anne at her home in Louisiana. Davis would recover from the malaria, though he would grieve for his first wife for years afterwards. Later after a trip to Havana, Cuba, he returned to Mississippi to become a planter.

In 1840, Davis first became involved in politics when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg, Mississippi and, to his surprise, was chosen as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson, Mississippi. In 1842, he attended the Democratic convention. In 1843, became a Democratic candidate for the State House of Representatives from the Warren County-Vicksburg district, an election he lost at the time. Davis was selected as one of six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election and campaigned effectively throughout Mississippi for the Democratic candidate James K. Polk.

In was also in 1844 that Davis met 18 year old Varina Anne Banks Howell, (1826-1906) whom his brother Joseph had invited for the Christmas season at Hurricane Plantation. She was a granddaughter of New Jersey Governor Richard Howell; her mother's family was from the South and included successful Scots-Irish planters. Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old widower Davis had asked Varina to marry him, and they became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics. The two were married on Wednesday, February 26, 1845.

|

| Jefferson and Varina Howell Davis in 1845 not long after their marriage. |

Jefferson and Varina Davis would have seven children; three of which died before reaching adulthood, and one who was possibly adopted by the Davis family.

Samuel Emory, born Saturday, July 30, 1852, and died Friday, June 30, 1854 from disease.

Margaret Howell was born Sunday, February 25, 1855, and died on Sunday, July 18, 1909, at the age of 54. She was the only child to marry and raise a family. She married Joel

Addison Hayes, Jr. (1848–1919), and they had five children together.

Jefferson Davis, Jr., was born Friday, January 16, 1857. He died at age 21 after contracting yellow fever in Wednesday, October 16, 1878, during an epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley that caused 20,000 deaths.

|

| The Davis children (left to right): Jefferson Davis Jr., Margaret Howell Davis, Varina "Winnie" Davis, and young William Howell Davis. Photo taken in 1867. |

William Howell, born on Friday, December 6, 1861, and he died of diphtheria at age 10 on Wednesday, October 16, 1872.

Varina Anne, known as "Winnie", was born on Monday, June 27, 1864, several months after her brother Joseph's death. She was known as the Daughter of the Confederacy as she was born during the war. After her parents refused to let her marry into a northern abolitionist family, she never married. She died nine years after her father, on Sunday, September 18, 1898, at age 34.

Jim Limber (sometimes referred to as Jim Limber Davis) was a bi-racial African-American child who was possibly adopted by the Davis family.

|

| Jim Limber Davis. |

On Sunday, February 14, 1864, Davis's wife, Varina Davis, was returning home in Richmond, Virginia, when she saw the boy being beaten and abused by an angry adult. Outraged, she immediately put an end to the beating and had the boy come with her in her carriage. He was cared for by Mrs. Davis and her staff. They gave him clothes belonging to the Davis's son, Joe, since the boys were of similar age. Davis officially had the boy registered as a Free Black. A touching story told by the family told how Jim comforted Davis following the tragic death of Joe. It is unknown if Davis actually adopted him. There was no adoption law in the State of Virginia at that time, so any adoption would likely have been an "extra-legal" matter. He lived in the Confederate White House with the Davis children, was their playmate and roommate, took his meals with them, wore the same clothes and played with same toys.

When the Davis's were later captured, the Union Army confiscated the child, literally ripping him from Varina's arms, and the Davis family never saw him again, though they did often speak fondly of him and question his whereabouts in letters to family and friends.

Davis was persuaded by the Democratic Party to become a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives and began canvassing for the election. In early October 1845 he traveled to Woodville, Mississippi to give a speech. He arrived a day early to visit his mother there, only to find that she had died the day before. After the funeral, he rode the 40 miles back to Natchez to deliver the news, then returned to Woodville again to deliver his speech. He won the election and entered the 29th U.S. Congress.

In 1846 the Mexican–American War began. Davis raised a volunteer regiment, the Mississippi Rifles, becoming its colonel under the command of his former father-in-law, General Zachary Taylor. On July 21 the regiment sailed from New Orleans for Texas. The regiment got its name because Colonel Davis armed his regiment with the M1841 Mississippi Rifle -- the first standard U.S. military rifle to use a percussion lock system and rifled barrels -- instead of the standard smoothbore flintlock muskets were still the primary infantry weapon of the U.S. Army at the time. U.S. President James Knox Polk had promised Davis the weapons if he would remain in Congress long enough for an important vote on the Walker tariff. The commanding U.S. General Winfield Scott objected on the basis that the weapons were insufficiently tested. Davis insisted and called in his promise from Polk, and his regiment was armed with the rifles, making it particularly effective in combat. The incident was the start of a lifelong feud between Davis and Scott.

During the war Davis participated in the Battle of Monterrey (September 21-24, 1846) during which he led the Mississippi Rifles in a successful charge on the El Fortin Del Teneria (Tannery Fort) along with a Tennessee regiment under Colonel William Campbell. On Wednesday, October 28, 1846, Davis formally resigned his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

On Monday, February 22, 1847, Davis fought bravely at the Battle of Buena Vista during which he was shot in the foot and then carried to safety by Robert H. Chilton, who would later serve as an aide in the Army of Northern Virginia under General Robert E. Lee.

On Monday, May 17th the same year, President Polk offered Davis a federal commission as a brigadier general and command of a brigade of militia. As a firm believer and advocate of States' Rights, Davis declined the appointment, arguing that the U.S. Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the individual States and not the federal government.

Following his return from the war, and in honor of his heroic service, Governor Albert G. Brown of Mississippi appointed him to the vacant position of United States Senator Jesse Speight, a Democrat, who had died on Saturday, May 1, 1847. Davis took his temporary seat on Wednesday, December 5th, and in January 1848 he was elected by the state legislature to serve the remaining two years of the term.

In December, during the 30th U.S. Congress, Davis was made a regent of the Smithsonian Institution. An enthusiastic supporter of the Smithsonian, Davis was a life-long friend of the institution's first Secretary, Joseph Henry (1797-1878) -- which would later lead to suspicions about the latter's loyalty to the Union.

The Senate made Davis chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs on Monday, December 3, 1849, during the first session of the 31st U.S. Congress. On Saturday, December 29th he was elected to a full six-year term by the Mississippi legislature. Davis had not served a year when he resigned in September 1851 to run for the governorship of Mississippi on the issue of the Compromise of 1850, which he opposed. He was defeated by fellow Senator Henry Stuart Foote. Left without political office, Davis continued his political activity. He took part in a convention on States' Rights, held at Jackson, Mississippi, in January of 1852. In the weeks leading up to the presidential election of 1852, he campaigned in numerous Southern states for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce and William R. King.

In 1853, after winning the presidential election, U.S. President Pierce made Davis his Secretary of War. Serving in that office, Davis began the Pacific Railroad Surveys in order to determine various possible routes for the proposed Transcontinental Railroad. He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona from Mexico in part to provide an easier southern route for the new railroad. The Pierce administration agreed and the land was purchased in December 1853. Davis would also be responsible for the construction of the Washington Aqueduct and the expansion of the U.S. Capital Building, all of which he personally oversaw.

Also in 1853, Davis would be responsible for convincing President Pierce to introduce camels into U.S. military service.

The idea was originally suggested to the War Department in 1836 by then U.S. Army Lieutenant George H. Crossman who, like Davis, Crossman also served in the Black Hawk War of 1832 before being transferred from the infantry to the Quartermaster Department. He submitted an extensive study on the subject to his superiors, proposing a U.S. Camel Corps. Crossman suggested that camels might be the right service animals for the harsh conditions in the American southwest.

Sometimes referred to as "the ship of the desert" camels can run as fast as 40 miles per hour in short bursts and sustain an average speed of around 25 miles per hour over great distances. Camels can also withstand long periods of time without water -- they can drink as seldom as once every ten days even in extremely hot climates, and can safely lost up to 30 percent of their body mass from dehydration. Their feet can also provide better traction over various types of terrain and soil than horses.

However, the Crossman report was largely ignored by the U.S. War Department, which had no interest in importing camels from Arabia. Later as a major, Crossman and fellow officer Major Henry C. Wayne took up the case for camels in U.S. service once again submitting a new report in 1847. This time it caught the eye of the forward-thinking Senator Davis who could see the benefit of using camels in the harsh, arid climates of the American desert west of the Rocky Mountains.

With the support of Davis, Congress finally approved the plan. On Saturday, March 3, 1855, $30,000 was appropriated to import camels for the U.S. military. Wayne was chosen to lead an expedition to the Middle East aboard the fittingly named USS Supply commanded by then U.S. Navy Lieutenant David Dixon Porter. They then purchased thirty-three camels: three in Tunisia, nine in Egypt, and twenty-one in Turkey. One camel was born on the return trip -- a total of twenty-four camels that arrived at Indianola, Texas on Wednesday, May 14, 1856.

These camel would then be herded to Camp Verde, Texas and began experimenting with their usefulness -- with a great deal of success. It took roughly five days for six mules to make the trip from Camp Verde to San Antonio transporting wagons carrying 1,800 pounds of oats, while the camels took only two days to cover the distance carrying 3,648 pounds (double the payload). Davis was pleased with the results. A second expedition to the Middle East would bring another 70 camels to the United States.

Unfortunately, the War Between The States (1861 - 1865) took the steam out of the experiment. During the war, camels were used to carry mail and transporting baggage. On an interesting note, at least one of these camels, named Old Douglas, would go on to serve in Company A, 43rd Mississippi Infantry Regiment C.S.A. -- which would be known as "The Camel Regiment." While some consideration was given to keeping the camels after the war, some U.S. government officials opposed the idea simply because Jefferson Davis previously supported it, and the camels eventually dispensed. Many were sold at auctions in 1864 and 1866 to work in circuses and mines, as postal carriers and pack animals and racing camels. Some even escaped, or were set free. Feral camels were occasionally spotted roaming the American Southwest for years after.

As Secretary of War, Davis also oversaw the increase of the U.S. Army and pay increase for the soldiers, which Congress agreed to and approved. Davis also introduced general usage of the rifles that he had used successfully during the Mexican-American War. As a result, both the morale and capability of the army was improved. Davis held this post for the full tenure of the Pierce presidency (4 years) and then won reelection to the Senate, returning to the body on Wednesday, March 4, 1857.

Davis's renewed service in the Senate was interrupted in early 1858 by an illness that began as a severe cold and which threatened him with the loss of his left eye. He was forced to remain in a darkened room for four weeks due to increased sensitivity to sunlight. Davis would suffer from poor health for most of the rest of his life, including repeated bouts of malaria and trigeminal neuralgia, a nerve disorder that causes severe pain in the face.

Despite being a staunch supporter of States' Right and slavery, Davis vehemently opposed the talk of secession from the Union in the later half of the 1850s. He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. On the Fourth of July, Davis delivered an anti-secessionist speech on board a ship near Boston. He again urged the preservation of the Union on October 11the same year in a speech at Faneuil Hall, Boston, and returned to the Senate soon after.

Jefferson Davis was a Southern plantation owner and owned about 113 African-American slaves in 1860, though for the times he lived in, he was known to be a fairly moderate slaveowner.

For example his slaves were allowed to govern themselves, they could chose their own overseer and decided their own work loads and schedules. They decided their own rules and punishments. Davis never interfered in their business unless he thought the punishments they meted out were too harsh for the infraction committed. They were well supplied, and they attended Church Services as they wished, often in the same Episcopal Church that the Davis's attended. They had free run of his vast library, and were allowed to learn to read and write if they wished -- which was technically against Mississippi State Law at the time. His first slave, James Pemberton, ran his plantation and maintained his home while he and the family were away on the business of the country.

As a U.S. Senator, Davis promoted the expansion of slavery across the American continent in order to balance political power with the industrial "free" Northern States; from proposing annexing several northern Mexico territories to the possible annexation of Cuba, none of which were supported by the Senate.

Ironically, in the summer of 1849, a group of Cuban revolutionaries led by Venezuelan adventurer Narciso Lopez wanted to capture the country from the Spanish. Lopez visited Davis and asked him to lead the expedition, offering an immediate payment of $100,000 (about 2 million dollars U.S. today), plus the same amount when Cuba was liberated. Davis declined the offer, stating that it was inconsistent with his duty as a U.S. Senator.

Like many other people at the time, Davis believed that each American state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the federal Union. The reason he opposed secession at the time was the belief the the rest of the Union would not allow the Southern States to peacefully withdraw. He also knew that the South lacked the ability to carry on a long war.

Ultimately, both of Davis' fears would be proven correct.

Despite all of his attempts to stop it, following the 1860 election of Republican Senator Abraham Lincoln, the State of Mississippi followed South Carolina and Alabama in withdrawing from the Union on Wednesday, January 9, 1861. Davis had expected this but waited until he received official notification on Monday, January 21, the day Davis called "the saddest day of my life." He delivered a farewell address to the U.S. Senate, resigned and returned to Mississippi.

Another irony of history happened at the Democratic National Convention of 1860 where future Union general Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts nominated Davis as a presidential candidate (the ninth of ten candidates), but who received only one vote on over fifty ballots from Butler himself. Just three years later during the war, Butler as a Union general, would become so infamous in his conduct occupying the captured city of New Orleans that Davis ordered him hanged as a war criminal without trial if ever captured.

Anticipating a call for his services since Mississippi had seceded, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Governor John J. Pettus saying, "Judge what Mississippi requires of me and place me accordingly." On Wednesdya, January 23, 1861, Pettus -- in recognition of his Mexican War service -- made Davis a major general of the Army of Mississippi.

On Monday, February 4, 1861 at the constitutional convention in Montgomery, Alabama he became a compromise candidate for the provisional presidency of the Confederacy and was so elected on Saturday, February 9, 1861 to wide acclaim by most of the convention.

Davis was the first choice because of his strong political and military credentials. He never actually wanted the job, hoping to instead serve as commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies, but said he would serve wherever directed. Varina Davis later wrote that when he received word that he had been chosen as president, "Reading that telegram he looked so grieved that I feared some evil had befallen our family."

He was inaugurated on Monday, February 18, 1861. Alexander H. Stephens was chosen as Vice President, but he and Davis feuded constantly due to both men having widely different social views on many issues and personality conflicts.

|

| Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederate States of America (1861-1865). Photograph by Matthew Brady courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

When Virginia seceded and joined the Confederacy, Davis moved his government to Richmond in May of 1861. The new Confederate First Family took up his residence there at the White House of the Confederacy

later that month. Davis would later be elected for a six-year term as

President of the newly formed Confederate States of America (CSA) on

Wednesday, November 6, 1861 following the ratification of a permanent Confederate Constitution and re-inaugurated on Saturday, February 22, 1862 -- George Washington's birthday.

As

the only president of the Confederacy,

Jefferson Davis proved to be something less

than the revolutionary leader necessary to lead a fledgling nation to

independence. As a peacetime president, Davis might have been the right

man to lead a newly established republic. As a wartime president, it

turned out not so much.

His interest in the military defense of his new country soon became

apparent. He treated his early war secretaries as little more than

clerks as he himself supervised the affairs of the department. He made

frequent forays into the battlefields, arriving at the First Battle of Manassas (Sunday, July 21, 1861) just as the fight was ending. Later he would arrive and be under fire at

the Battle of Seven Pines (Sunday, June 1, 1862) where he placed his military adviser, General Robert E. Lee, in command of what became the

Army of Northern Virginia after General Joseph E. Johnston was wounded.

Later he toured the western theater where he supported his old friend, General Braxton Bragg against the -- usually justified -- criticisms of his subordinates. His handling of the high command was extremely controversial. While his relationship with General Lee, however, was perhaps one of America's best examples of a military and civilian leadership cooperating, there were long-standing feuds with Generals P.G.T. Beauregard, Joe Johnston, and Daniel Harvey Hill. His defense of certain non-performing generals, such as Bragg, irritated many in the South.

Perhaps most ironically, Davis -- a firm believer in states' rights -- ran his country as Confederate President in a somewhat autocratic way because of his attempt to manage the war himself, placing more power in the hands of the central government authority. This in turn led to a large and well-organized anti-Davis faction in the Confederate Congress, especially in the Senate. The Confederacy had no political parties, so Davis found himself with few political allies outside of his own cabinet.

During the war, Davis would continued to enjoy less and less popularity from those in congress, especially after using the very first veto power of the Confederate Constitution to nullify an attempt by the more hard-liners on slavery in the congress from reopening the international slave trade -- a violation of Article I Section 9(1) of the Confederate Constitution.

To be completely fair to Davis, the task of defending the Confederacy against the much stronger Union would have been a great challenge for any leader under the circumstances. Could someone other than Davis have done a better job of keeping an alliance of several States together while conducting a war for independence? Probably so, but then again Davis himself didn't want the job in the first place, though felt honor bound to carry out the task given to him to the best of his limited abilities.

Despite his best efforts, and perhaps in some cases because of some of his inability to compromise with some Confederate generals previously mentioned, the Confederacy fell apart in spring of 1865. Davis was forced to abandon Richmond and flee south to escape Union cavalry in hot pursuit (see my article on the flight of Jefferson Davis HERE).

After five weeks on the run, Davis, his family, and the remainder of his cabinet were surrounded and captured by forces of the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry and the 4th Michigan Cavalry near Irwinville, Georgia in the early morning hours of Wednesday, May 10, 1865. Today a monument marks the spot of Davis' arrest located at the Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site.

The now former President Davis was taken to Fortress Monroe at Hampton, Virginia and held there without trial for two years, under the charges of conspiring to assassinate Lincoln and treason. Leg irons were riveted to his ankles at the order of Major General Nelson A. Miles, who was in charge of the fort. Davis was allowed no visitors, and no books except the Bible. Davis remained in a small cell in one of the fort's casemates from May 22 - October 2, 1865 with two guards that never spoke to him present inside the cell at all times, and one outside the door.

The physician attending to him, Dr. John J. Craven, objected to the willful neglect and abuse Davis suffered. In addition to his previously mentioned trigeminal neuralgia, Davis suffered from a number of ailments during his imprisonment: headaches, erysipelas, an ulcerated cornea of the eye, dyspepsia, and severe depression. Despite being a former Union soldier -- a surgeon with the Union Army of the Potomac's Tenth Corps -- Craven attended to Davis successfully and mitigated his harsh imprisonment. He was then moved to Carroll Hall inside the fort for the remainder of his stay at Fort Monroe.

In 1866, Craven would publish a book The Prison life of Jefferson Davis, which led to increased sympathy for the former Confederate President with the American public in the north.

Varina and their young daughter, Winnie, were allowed to join Davis, and the family was eventually given an apartment in the officers' quarters for a time before the family moved to Canada.

Pope Pius IX after learning that Davis was a prisoner, sent him a portrait inscribed with the Latin words: "Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis, et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus", which correspond to Matthew 11:28 KJV, "Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you, sayeth the Lord". A hand-woven crown of thorns associated with the portrait is often said to have been made by the Pope, though likely woven by Varina Davis.

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released in May of 1867 on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith -- the latter of which had been a member of the Secret Six who financially supported the fanatical abolitionist terrorist John Brown.

On Monday, June 11, 1866 the House of Representatives voted, 105-19, to support such a trial against Davis. Although Davis himself wanted such a trial, there would ultimately be no treason trials against anyone as it was felt they would probably not turn out in favor of the U.S. government and would impede national reconciliation

At the start of the troubles between the North and the South, Jefferson Davis had initially been against secession, and he argued in both venues trying to prevent it. In the end, when no compromise could be reached, Davis followed the Military Oath that he and all West Point Cadets took at graduation, which at the time was not an oath to the United States, but an oath to defend and protect their Home State from all enemies, both foreign and domestic. There was no 'treason', he was not a 'traitor', and he did not violate his Military Oath.

There was also a concern at the time that such action could result in a judicial decision that would validate the constitutionality of secession as they believed that the evidence would show the prosecution baseless and illegal. This fear would later removed by the Supreme Court ruling in Texas v. White (1869) declaring secession unconstitutional.

Davis remained under indictment until U.S. President Andrew Johnson issued on Christmas Day of 1868 a presidential "pardon and amnesty" for the offense of treason to "every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late insurrection or rebellion" and after a federal circuit court on Monday, February 15, 1869 dismissed the case against Davis after the government's attorney informed the court that he would no longer continue to prosecute Davis. Although he was not tried, he was stripped of his eligibility to run for public office.

Davis went to Montreal, Quebec to join his family and lived in Lennoxville, Quebec until 1868, later visiting Cuba and Europe in search of work. At one stage he stayed as a guest of James Smith, a foundry owner in Glasgow, who had struck up a friendship with Davis when he toured the Southern States promoting his foundry business.

In 1869, Davis became president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Memphis, Tennessee, at an annual salary of $12,000. Upon General Robert E. Lee's death, Davis agreed to preside over the Presbyterian memorial in Richmond on Thursday, November 3, 1870. That speech prompted further invitations, although he declined them until July 1871, when he was commencement speaker at the University of the South. Like many other white Southerners and former Confederates, Davis resented the military occupation of the Southern States and the radical Reconstruction policies of the ruling Republican Party.

By the late 1880s following the end of Reconstruction, Davis began to encourage reconciliation between the North and South, telling Southerners to be loyal citizens to the Union. According to the Meriden Daily Journal, at a reception held in New Orleans in May 1887, Davis urged southerners to be loyal to the nation, saying: "United you are now, and if the Union is ever to be broken, let the other side break it."

Davis was helped in the last decade of his life by the generosity of a wealthy widow, Miss Sarah Anne Dorsey, when she invited him to her plantation, Beauvoir, near Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1877. At a time when he was once again sick, and gave him a cottage on the land to use while working on his memoir. She gave Davis her plantation before her death in 1878, and she also gave him a fund for his family's support.

Always contentious, Davis wrote his autobiography entitled: The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. In this 1881 work he re-fought the war, including his views of those feuds with officers like Beauregard and Johnston who received much of the blame for the Confederacy's demise. In 1889, shortly before his death, he wrote his final book: A Short History of the Confederate States of America where he expressed his firmly held believed that Confederate secession was constitutional, and was optimistic concerning American prosperity and the next generation.

Davis would continue to live in some comfort with his wife until his death on Wednesday, December 6, 1889 in New Orleans, Louisiana at the home of Charles Erasmus Fenner, a former Confederate officer who became an Associate Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court after suffering from acute bronchitis complicated by the malaria he suffered off and on his whole life. He died holding his wife's hand. He was 81 years old.

His funeral was one of the largest in the South, and New Orleans draped itself in mourning as his body lay in state in the City Hall for several days. An Executive Committee decided to emphasize Davis's ties to the United States, so an American national flag was placed over the Confederate flag during the viewing, and many crossed American and Confederate flags nearby. Davis wore a new suit of Confederate grey fabric Confederate General Jubal Early had given him, and Varina placed a sword Davis had carried during the Black Hawk War on the bier.

At the death of Davis, some of

his former slaves and tenants wrote a letter of condolence to his widow,

which is still in existence today. It reads: "Brierfield Miss, Dec

12, 1889; To Mrs. Jefferson Davis, Beauvoir, Miss; We, the old servants

and tenants of our beloved master, Hon. Jefferson Davis, have cause to

mingle our tears over his death, who was always so kind and thoughtful

for our peace and happiness, we extend to you our humble sympathy.

Respectfully yours, old tenants and servants, Ned Gaitor, Tom McKinney,

Grant McKinney, Mary Pemberton, Mary Archer, Eliza. Norris, Grant

Ketchens, Teddy Everson, Hy Garland, Louisa Nick, Wm. Grear, Guss

Williams, and others."

While in the Confederate White House in Richmond, Davis's personal valet was an African-American man, Mr. James H. Jones. He was captured with Davis and sent to prison with him at Fortress Monroe, and was held there for one month. At Davis's death, Mr. Jones drove the carriage that carried Davis's coffin, and stated he had lost his best friend. Later in life, Mr. Jones would also transport the bodies of Varina Davis and their daughter, Winnie, upon their passing. Varina Davis had given Jones a cane which had belonged to Davis, and she'd had it inscribed for Jones. Mr. Jones later gave that cane to the state of North Carolina where he lived, and was placed in the North Carolina Museum of History.

Although initially laid to rest in New Orleans in the Army of Northern Virginia tomb at Metairie Cemetery, in 1893 Davis was reinterred in Richmond, Virginia at Hollywood Cemetery, per Varina's request. A life sized statue of Davis was eventually erected as promised by the Jefferson Davis Monument Association, in cooperation with the Southern Press Davis Monument Association, the United Confederate Veterans and ultimately the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The monument's cornerstone was laid in an 1896 ceremony, and it was dedicated with great pomp and 125,000 spectators on Monday, June 3, 1907, the last day of a Confederate reunion. Despite his service as the only president of the Confederate States of America, his grave marker makes no mention of this, only his accomplishment as a U.S. Senator and his service in the U.S. Army in the Mexican War.

Davis and his family all rest in the plot to this day.

After Jefferson Davis' death in 1889, Beauvoir was passed on to Varina who sold most of the property to the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, to be used as home for aged Confederate veterans

and widows. The SCV built a

dozen barracks buildings, a hospital, and a chapel behind the main

house. From 1903 to 1957, approximately 2,500 former Confederate veterans and their

families lived at the home. Many of these veterans were buried in a cemetery on

the property. Today the old home is the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Confederate Soldier and the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library and Museum.

Although he never received an official restoration of his citizenship during his lifetime -- nor particularly desired one -- the U.S. Senate passed Joint Resolution 16 on Tuesday, October 17, 1978 officially restoring Jefferson Davis' United States citizenship. This was signed into law by U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

Later he toured the western theater where he supported his old friend, General Braxton Bragg against the -- usually justified -- criticisms of his subordinates. His handling of the high command was extremely controversial. While his relationship with General Lee, however, was perhaps one of America's best examples of a military and civilian leadership cooperating, there were long-standing feuds with Generals P.G.T. Beauregard, Joe Johnston, and Daniel Harvey Hill. His defense of certain non-performing generals, such as Bragg, irritated many in the South.

Perhaps most ironically, Davis -- a firm believer in states' rights -- ran his country as Confederate President in a somewhat autocratic way because of his attempt to manage the war himself, placing more power in the hands of the central government authority. This in turn led to a large and well-organized anti-Davis faction in the Confederate Congress, especially in the Senate. The Confederacy had no political parties, so Davis found himself with few political allies outside of his own cabinet.

During the war, Davis would continued to enjoy less and less popularity from those in congress, especially after using the very first veto power of the Confederate Constitution to nullify an attempt by the more hard-liners on slavery in the congress from reopening the international slave trade -- a violation of Article I Section 9(1) of the Confederate Constitution.

To be completely fair to Davis, the task of defending the Confederacy against the much stronger Union would have been a great challenge for any leader under the circumstances. Could someone other than Davis have done a better job of keeping an alliance of several States together while conducting a war for independence? Probably so, but then again Davis himself didn't want the job in the first place, though felt honor bound to carry out the task given to him to the best of his limited abilities.

Despite his best efforts, and perhaps in some cases because of some of his inability to compromise with some Confederate generals previously mentioned, the Confederacy fell apart in spring of 1865. Davis was forced to abandon Richmond and flee south to escape Union cavalry in hot pursuit (see my article on the flight of Jefferson Davis HERE).

After five weeks on the run, Davis, his family, and the remainder of his cabinet were surrounded and captured by forces of the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry and the 4th Michigan Cavalry near Irwinville, Georgia in the early morning hours of Wednesday, May 10, 1865. Today a monument marks the spot of Davis' arrest located at the Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site.

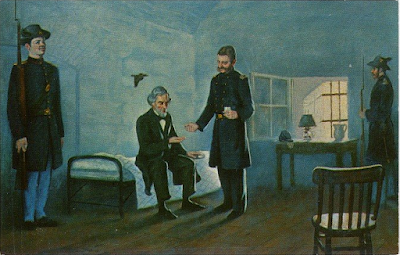

The now former President Davis was taken to Fortress Monroe at Hampton, Virginia and held there without trial for two years, under the charges of conspiring to assassinate Lincoln and treason. Leg irons were riveted to his ankles at the order of Major General Nelson A. Miles, who was in charge of the fort. Davis was allowed no visitors, and no books except the Bible. Davis remained in a small cell in one of the fort's casemates from May 22 - October 2, 1865 with two guards that never spoke to him present inside the cell at all times, and one outside the door.

The physician attending to him, Dr. John J. Craven, objected to the willful neglect and abuse Davis suffered. In addition to his previously mentioned trigeminal neuralgia, Davis suffered from a number of ailments during his imprisonment: headaches, erysipelas, an ulcerated cornea of the eye, dyspepsia, and severe depression. Despite being a former Union soldier -- a surgeon with the Union Army of the Potomac's Tenth Corps -- Craven attended to Davis successfully and mitigated his harsh imprisonment. He was then moved to Carroll Hall inside the fort for the remainder of his stay at Fort Monroe.

In 1866, Craven would publish a book The Prison life of Jefferson Davis, which led to increased sympathy for the former Confederate President with the American public in the north.

|

| A portrait of Jefferson Davis as a prisoner at Fort Monroe (1865 - 1867) being tended to by Dr. John J. Craven. Note the two armed guards in his room. |

Varina and their young daughter, Winnie, were allowed to join Davis, and the family was eventually given an apartment in the officers' quarters for a time before the family moved to Canada.

Pope Pius IX after learning that Davis was a prisoner, sent him a portrait inscribed with the Latin words: "Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis, et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus", which correspond to Matthew 11:28 KJV, "Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you, sayeth the Lord". A hand-woven crown of thorns associated with the portrait is often said to have been made by the Pope, though likely woven by Varina Davis.

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released in May of 1867 on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith -- the latter of which had been a member of the Secret Six who financially supported the fanatical abolitionist terrorist John Brown.

On Monday, June 11, 1866 the House of Representatives voted, 105-19, to support such a trial against Davis. Although Davis himself wanted such a trial, there would ultimately be no treason trials against anyone as it was felt they would probably not turn out in favor of the U.S. government and would impede national reconciliation

At the start of the troubles between the North and the South, Jefferson Davis had initially been against secession, and he argued in both venues trying to prevent it. In the end, when no compromise could be reached, Davis followed the Military Oath that he and all West Point Cadets took at graduation, which at the time was not an oath to the United States, but an oath to defend and protect their Home State from all enemies, both foreign and domestic. There was no 'treason', he was not a 'traitor', and he did not violate his Military Oath.

There was also a concern at the time that such action could result in a judicial decision that would validate the constitutionality of secession as they believed that the evidence would show the prosecution baseless and illegal. This fear would later removed by the Supreme Court ruling in Texas v. White (1869) declaring secession unconstitutional.

Davis remained under indictment until U.S. President Andrew Johnson issued on Christmas Day of 1868 a presidential "pardon and amnesty" for the offense of treason to "every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late insurrection or rebellion" and after a federal circuit court on Monday, February 15, 1869 dismissed the case against Davis after the government's attorney informed the court that he would no longer continue to prosecute Davis. Although he was not tried, he was stripped of his eligibility to run for public office.

Davis went to Montreal, Quebec to join his family and lived in Lennoxville, Quebec until 1868, later visiting Cuba and Europe in search of work. At one stage he stayed as a guest of James Smith, a foundry owner in Glasgow, who had struck up a friendship with Davis when he toured the Southern States promoting his foundry business.

In 1869, Davis became president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Memphis, Tennessee, at an annual salary of $12,000. Upon General Robert E. Lee's death, Davis agreed to preside over the Presbyterian memorial in Richmond on Thursday, November 3, 1870. That speech prompted further invitations, although he declined them until July 1871, when he was commencement speaker at the University of the South. Like many other white Southerners and former Confederates, Davis resented the military occupation of the Southern States and the radical Reconstruction policies of the ruling Republican Party.

|

| Jefferson Davis later in his life. |

By the late 1880s following the end of Reconstruction, Davis began to encourage reconciliation between the North and South, telling Southerners to be loyal citizens to the Union. According to the Meriden Daily Journal, at a reception held in New Orleans in May 1887, Davis urged southerners to be loyal to the nation, saying: "United you are now, and if the Union is ever to be broken, let the other side break it."

Davis was helped in the last decade of his life by the generosity of a wealthy widow, Miss Sarah Anne Dorsey, when she invited him to her plantation, Beauvoir, near Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1877. At a time when he was once again sick, and gave him a cottage on the land to use while working on his memoir. She gave Davis her plantation before her death in 1878, and she also gave him a fund for his family's support.

Always contentious, Davis wrote his autobiography entitled: The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. In this 1881 work he re-fought the war, including his views of those feuds with officers like Beauregard and Johnston who received much of the blame for the Confederacy's demise. In 1889, shortly before his death, he wrote his final book: A Short History of the Confederate States of America where he expressed his firmly held believed that Confederate secession was constitutional, and was optimistic concerning American prosperity and the next generation.

Davis would continue to live in some comfort with his wife until his death on Wednesday, December 6, 1889 in New Orleans, Louisiana at the home of Charles Erasmus Fenner, a former Confederate officer who became an Associate Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court after suffering from acute bronchitis complicated by the malaria he suffered off and on his whole life. He died holding his wife's hand. He was 81 years old.

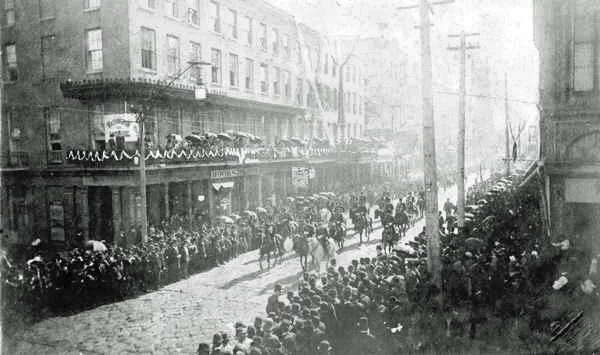

|

| Jefferson Davis' funeral procession in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1889. Members of the United Confederate Veterans and the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) were honor guards in the procession. |

His funeral was one of the largest in the South, and New Orleans draped itself in mourning as his body lay in state in the City Hall for several days. An Executive Committee decided to emphasize Davis's ties to the United States, so an American national flag was placed over the Confederate flag during the viewing, and many crossed American and Confederate flags nearby. Davis wore a new suit of Confederate grey fabric Confederate General Jubal Early had given him, and Varina placed a sword Davis had carried during the Black Hawk War on the bier.

|

| Mr. James H. Jones, President Davis' personal valet. |

While in the Confederate White House in Richmond, Davis's personal valet was an African-American man, Mr. James H. Jones. He was captured with Davis and sent to prison with him at Fortress Monroe, and was held there for one month. At Davis's death, Mr. Jones drove the carriage that carried Davis's coffin, and stated he had lost his best friend. Later in life, Mr. Jones would also transport the bodies of Varina Davis and their daughter, Winnie, upon their passing. Varina Davis had given Jones a cane which had belonged to Davis, and she'd had it inscribed for Jones. Mr. Jones later gave that cane to the state of North Carolina where he lived, and was placed in the North Carolina Museum of History.

|

| Jefferson Davis' cane given to Mr. James H. Jones, his African- American valet after his death, is now on display at the North Carolina Museum of History. |

Although initially laid to rest in New Orleans in the Army of Northern Virginia tomb at Metairie Cemetery, in 1893 Davis was reinterred in Richmond, Virginia at Hollywood Cemetery, per Varina's request. A life sized statue of Davis was eventually erected as promised by the Jefferson Davis Monument Association, in cooperation with the Southern Press Davis Monument Association, the United Confederate Veterans and ultimately the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The monument's cornerstone was laid in an 1896 ceremony, and it was dedicated with great pomp and 125,000 spectators on Monday, June 3, 1907, the last day of a Confederate reunion. Despite his service as the only president of the Confederate States of America, his grave marker makes no mention of this, only his accomplishment as a U.S. Senator and his service in the U.S. Army in the Mexican War.

Davis and his family all rest in the plot to this day.

| The grave of President Jefferson Davis and his family at Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, USA. |

Although he never received an official restoration of his citizenship during his lifetime -- nor particularly desired one -- the U.S. Senate passed Joint Resolution 16 on Tuesday, October 17, 1978 officially restoring Jefferson Davis' United States citizenship. This was signed into law by U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

No comments:

Post a Comment