This blog post is dedicated to

recognition and memory of the men and boys from Fort Mill, South

Carolina who served in the United States armed forces during the First World War (1914-1918) and in honored memory of those that made the

supreme sacrifice in service to their duty.

Sergeant James E. Bailes

1st Lieutenant James C. Dozier

Private Carey L. Farris

Private William Gray

Sergeant Thomas Lee Hall

Private Leonard Jennings

Private Walter O. Leazer

Corporal Harvey F. McManus

Corporal Fred T. Miller

Private William G. Patterson

Private William O. Purser

Private Seth E. Robbins

Private Eugene S. Ross

Private Clyde W. Stevens

Private St. Clair Sutton

Sergeant James E. Bailes

1st Lieutenant James C. Dozier

Private Carey L. Farris

Private William Gray

Sergeant Thomas Lee Hall

Private Leonard Jennings

Private Walter O. Leazer

Corporal Harvey F. McManus

Corporal Fred T. Miller

Private William G. Patterson

Private William O. Purser

Private Seth E. Robbins

Private Eugene S. Ross

Private Clyde W. Stevens

Private St. Clair Sutton

Veterans Park is located at 106 North White Street not very far from the Confederate Park on Main Street in downtown Fort Mill, South Carolina -- in fact about fifty or sixty yards, or so, across the railroad tracks. Surrounded by green space, this park is centered around a beautiful monument that honors the memories and sacrifices of those men and boys from Fort Mill that served in the First World War (1914-1918).

In some ways its fitting that the monument honoring the soldiers of what was then termed the Great War should sit a good stone throw away from the monuments honor the Confederate veterans themselves. Many of those who served from Fort Mill when the United States entered the war on Friday, April 6, 1917 were the sons and grandsons of the veterans who wore the gray and butternut of the Confederate soldier and were likely inspired by the same devotion to duty passed down through the generations.

When the U.S. government and State of South Carolina called up their sons to join up and go fight the German Kaiser's invading hordes in Western Europe, many were all-too eager to join the fight and put on the khaki uniforms of the American Doughboy -- the popular nickname for American servicemen at the time. It was a young army too as nearly sixty percent of U.S. servicemen who volunteered were between the ages of 17 to 25!

Of the 123 young men from this small Southern town in the Piedmont region of South Carolina who went off to fight in World War I, fifteen of them did not return.

The park’s centerpiece is an 8-foot tall pedestal topped by a World War I soldier. The pedestal is engraved with the names of fallen Fort Mill servicemen and women. Five granite walls in the shape of a five-point star represent the five branches of the uniformed services. In addition there are eight flag poles which fly the flags of the United States of America, the State of South Carolina, the five branches of the U.S. Armed Forces, and the POW-MIA Flag.

The American Legion Post 43 and the Veterans Of Foreign Wars Post 9138 of Fort Mill contributed to the creation of this park and monument in everlasting memory of these men.

|

| World War One Soldiers Monument in downtown Fort Mill, SC, USA. |

|

| The monument lists the names of three major local World War I heroes. Among them a World War I fighter ace and Distinguished Service Cross winner and two posthumous Medal of Honor winners. |

|

| The names of World War One veterans engraved on red bricks at the base of the monument. Around these are the logos of the five U.S. Armed Services branches. |

Many of the men and boys represented by this monument are buried in Fort Mill's Unity Cemetery among other local veterans of America's wars, while others are buried in plots with other foreign servicemen in France and Belgium where they fell in battle.

A small plot in the cemetery with a beautiful stone monument marks the graves of six local men buried there -- including one posthumous Medal of Honor winner, Sergeant Thomas Lee Hall (1893-1918), who'd previously served in the Mexican Border Campaign of 1916. All of them were members of Company G, 118th Infantry, 30th Division of the U.S. Expeditionary Forces killed during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (September 26 - November 11, 1918) a major part of the Hundred Days Offensive (August 8 - November 11, 1918) -- the final major Allied offensive of the War on the Western Front in Belgium and France that broke the Hindenburg Line.

|

| The grave of Elliott White Springs, who served as a flying ace in World War I. He buried with his wife, Frances, and son, Leroy. |

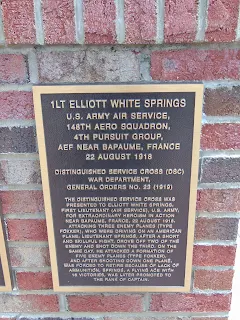

Probably the most well known person to serve in the war from Fort Mill was Mr. Elliott White Springs (1896-1959) who served as a World War I fighter pilot between 1917-1918. Springs was the grandson of local Civil War veteran, Captain Samuel Elliott White (1837-1911) the founder of downtown Fort Mill's Confederate Park.

At the rank of 1st Lieutenant, Springs became the 5th ranked US Fighter Ace of the war credited with shooting down 16 enemy aircraft and becoming a Squadron Commander and a captain at the age of 22. He was awarded the U.K. Distinguished Flying Cross and the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross.

Springs survived the war and would later return to military service as in World War II in the US Army Air Corps and retire as a lieutenant colonel.

At the rank of 1st Lieutenant, Springs became the 5th ranked US Fighter Ace of the war credited with shooting down 16 enemy aircraft and becoming a Squadron Commander and a captain at the age of 22. He was awarded the U.K. Distinguished Flying Cross and the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross.

Springs survived the war and would later return to military service as in World War II in the US Army Air Corps and retire as a lieutenant colonel.

|

| Elliott White Springs photographed smiling in front of his crashed Sopwith Camel fighter plane at the Remaisnil Aerodrome (France) of the 148th Aero Squadron on Monday, September 16, 1918. (Courtesy of The Springs-Close Family Archives, Fort Mill, SC.) |

Included among those men and boys of Fort Mill who served in the war, 25 of these were African-Americans.

Nearly 200,000 black Americans served in World War I, mostly in service positions -- largely due to the prejudices at the time in the country that African-Americans were better suited to manual labor than combat roles. Most of these men were part of the American Expeditionary Forces Service of Supply (SOS) which transported supplies, dug trenches, cleaned latrines and debris, and buried corpses. Thought not an unimportant job by any means, it was likely far less "glamorous" than combat.

Other black U.S. servicemen, including eight individuals from Fort Mill, became members of the 92nd and 93rd U.S. Infantry Divisions, both segregated infantry divisions with white officers who were both "loaned" the the French army and fought in the trenches on the Western Front wearing French helmets and issues French military rifles. Despite this, both divisions fought extremely well and won a number of awards for bravery in the final year of the war in 1918.

Probably the most notable black Doughboy from Fort Mill was Private Ishmong Edwards, who fought with the 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the "Harlem Hellfighters."

The 369th served an impressive 191 consecutive days in the trenches -- more than any other American unit. They also suffered the most losses of any American regiment with about 1,500 casualties. This regiment was also the first of the Allied forces to reach the Rhine River following the Armistice of Monday, November 11, 1918. The French government awarded the Croix de Guerre to 170 individual members of the 369th (the first Americans to receive that award), and a unit citation was awarded to the entire regiment. One Medal of Honor and numerous Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to members of the regiment.

Nearly 200,000 black Americans served in World War I, mostly in service positions -- largely due to the prejudices at the time in the country that African-Americans were better suited to manual labor than combat roles. Most of these men were part of the American Expeditionary Forces Service of Supply (SOS) which transported supplies, dug trenches, cleaned latrines and debris, and buried corpses. Thought not an unimportant job by any means, it was likely far less "glamorous" than combat.

Other black U.S. servicemen, including eight individuals from Fort Mill, became members of the 92nd and 93rd U.S. Infantry Divisions, both segregated infantry divisions with white officers who were both "loaned" the the French army and fought in the trenches on the Western Front wearing French helmets and issues French military rifles. Despite this, both divisions fought extremely well and won a number of awards for bravery in the final year of the war in 1918.

Probably the most notable black Doughboy from Fort Mill was Private Ishmong Edwards, who fought with the 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the "Harlem Hellfighters."

The 369th served an impressive 191 consecutive days in the trenches -- more than any other American unit. They also suffered the most losses of any American regiment with about 1,500 casualties. This regiment was also the first of the Allied forces to reach the Rhine River following the Armistice of Monday, November 11, 1918. The French government awarded the Croix de Guerre to 170 individual members of the 369th (the first Americans to receive that award), and a unit citation was awarded to the entire regiment. One Medal of Honor and numerous Distinguished Service Crosses were awarded to members of the regiment.

No comments:

Post a Comment