|

| Photograph taken in downtown York, South Carolina on Thursday, July 4, 1867, showing a large number of African-Americans citizens celebrating U.S. Independence Day along with Union soldiers of the Reconstruction occupation forces. Image courtesy of the Culture & Heritage Museum, York County, SC. |

The Lynchings of Jim Williams & Elias Hill

Reconstruction Era Terror In York County, South Carolina

By C.W. Roden

Now as many of y'all know, this writer is a proud Southern man and a defender of the culture, heritage and history of this place I call home. Believe me there is much about the South that I'm deeply proud of will defend to my dying breath.

That being said, I will also tell y'all that there is also as much about the land of my birth, and the history of America, that I'm just as equally ashamed of too. Stories and incidents that I'm more than willing to call out and talk about.

To appreciate the good things all the more, one has to confront the bad things. The story I am going to relate to y'all today is perhaps one of the darkest moments in the local history of my little corner of South Carolina.

Just after midnight on Monday, March 6, 1871, a group of black-clad riders arrived at the cabin home of Jim and Rose Williams and demanded that Jim, a former Union soldier and local militia captain, surrender to them.

This incident in York County would be one of the most infamous crimes carried out by the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan and would have serious far-reaching repercussions, not just in York County in the 19th century, but across America as a whole long afterwards.

It took place during one of the most turbulent times in South Carolina's history: The Reconstruction Era (1867-1877).

Reconstruction & Occupation

Following the War Between The States (1861-1865) South Carolina was once again under military occupation. This time not by red and green-coated British soldiers and their American Loyalist collaborators, but by American men wearing the blue coats of the Union Army and their pro-Union allies.

In June 1865, he appointed Benjamin Franklin Perry of South Carolina as the provisional governor of the state. In September of the same year, an all-white constitutional convention met in the state capital in Columbia to formally repeal the 1860 Ordinance of Secession and to recognize the federal abolition of slavery. This convention also enacted so-called Black Codes, discriminatory laws that severely restricted former African-American slaves to a social and economic status that echoed antebellum slavery.

In Congress, the radical abolitionist wing of the Republican Party took control of Reconstruction. They impeached and tried President Johnson for his lenient attitude toward the defeated Southern States -- this despite the fact that President Lincoln himself intended to do much of the same thing prior to his assassination. Johnson would ultimately win the trial by a single vote, but his authority was relegated to lame-duck status for the remainder of his single term in office.

However, this did not stop Johnson from issuing a general pardon to all former Confederate soldiers who fought in that conflict on Christmas day of 1868. In his proclamation, the president unconditionally and without reservation extended to all former Confederates (including Jefferson Davis and other government officials) "....a full pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason [sic] against the United States, or of adhering to their enemies during the late Civil War, with restoration of all rights, privileges, and immunities under the Constitution and the laws."

Again this was something that Lincoln himself planned to do for the most part, although unlike Johnson, he advocated in his final public speeches for the full citizenship and right to vote for former slaves.

On Tuesday, December 8, 1863, in his annual message to Congress, Lincoln had outlined his plans for reconstruction of the South, including amnesty terms for former Confederates except for those who had held office in the Confederate government at that time, or persons who had mistreated Union prisoners. A pardon would require an oath of allegiance, but it would not restore ownership to former slaves, or restore confiscated property that involved a third party. However, the radical Republicans, who held full control of the legislative agenda in Congress, objected to Lincoln's plans as far too lenient and refused to recognize delegates from the reconstructed governments of Louisiana and Arkansas. Congress instead passed the Wade-Davis Bill. This measure required half of any former Confederate State’s voters to swear allegiance to the United States and that they had not supported the Confederacy. While the Wade-Davis Bill also ended slavery, it did not allow former slaves to vote.

Lincoln vetoed the bill.

Even as late as 1865, with the war finally coming to a close, Lincoln planned to quickly restore the former Confederate States to the Union and full U.S. citizenship to the citizens of those states -- including the former slaves themselves.

In 1865, Union Major General William T. Sherman, under Lincoln's directive, issued Special Field Orders No. 15, seizing land from white owners in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida to settle 40,000 freed slaves and black refugees. This was the basis of the phrase "40 acres and a mule" and was revoked a year later by President Johnson.

Unlike the weaker Johnson, Lincoln had the popularity and the political clout at that point to push through his plans for a fully restored Union; plans that died with him and ultimately set the stage for the incompetent corruption and reactionary terror that would soon follow.

Following Johnston's impeachment, the radical Republicans placed ten of the former Confederate States under military occupation and dispatched Union troops to enforce civil rights and election laws.

The first of the four Federal Reconstruction Acts was passed by the U.S. Congress on Saturday, March 2, 1867 after overriding a presidential veto. It divided the former Confederate States (with the exception of Tennessee) into five military occupation districts and gave the right to vote only to black males and whites who were either loyal to the Union during the War Between The States, or those who had moved to the south after 1860.

By 1868, a second constitutional convention met in Charleston, South Carolina; this time with a black majority and white Republicans appointed by the Union occupation forces controlling the convention. The 1868 State Constitution was a somewhat more progressive document that did strengthen county government and public schools, end debtor's prisons, and also legalized divorce. It would remain in effect until 1895.

The election of 1868 also saw the election of Radical Republicans and a number of African-Americans to local public offices. This was done largely by newly enfranchised former slaves organized and registered by pro-Union voting leagues while former Confederates remained disenfranchised until Christmas of that same year.

This election would unfortunately prove be the beginning of the end to a relatively small, but tense, peaceful relations between black and white citizens of South Carolina. Disenfranchised and suffering military occupation, some Democrats and many former Confederate veterans abandoned conventional politics to the Republicans and waged a campaign of extra-legal intimidation.

This would also lead to the rise of some of the ugliest civil violence in upstate South Carolina since 1780.

Jim Williams was an African-American militia leader in South Carolina’s York County.

Williams (born James Rainey) had been born sometime in 1830 as a slave on the Rainey Plantation about 10 miles west of Rock Hill in York County near modern-day Brattonsville.

Williams, who worked as a cook on the plantation, ran away during the later half of the War Between the States and later fought for the Union as a member of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Williams served for 18 months under Union General William T. Sherman's command during his march through the Carolinas in 1865.

After the war, Williams returned to York County on Friday, May 4, 1866 still wearing his blue Union uniform and organized a local black militia organization which sought to protect black rights in the area becoming its captain. This militia was backed up and supported by the local Union occupation forces.

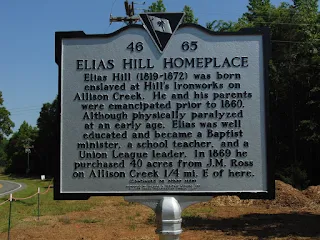

Assisting Captain Williams was another local black civil rights activist in York County, Elias Hill.

Hill was born in 1819 to Dorcas and Elias Hill in York County at the iron works of the famous Hill family (the descendants of local Revolutionary War hero Colonel William Hill).

In 1826 at the age of 7, young Hill was stricken with a debilitating neurological disease (possibly polio, or muscular dystrophy) which left him crippled in one arm and one leg.

In spite of his weakened body, Hill had a sharp mind and was eager to learn. No one objected to having a deformed child hanging around the local school. Because of his condition he was ridiculed by the children, but it also afforded him the opportunity to become educated. The white school children taught Elias to read and write contrary to the laws prohibiting African-Americans from being educated at the time.

One of the children who helped educate Elias Hill was a member of the white family that owned him, and future Confederate General Daniel Harvey Hill. (In another interesting and ironic twist in history, Hill's future brother-in-law and fellow Confederate General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson would also defy the laws of his own native State of Virginia and educate black children.)

Because of his childhood illness, as an adult, his legs remained extremely skinny, his arms were withered, and his jaw was deformed. Hill also seemed to suffer from a form of dwarfism.

After the War ended in 1865, Hill worked and became an ordained Baptist minister moving from congregation to congregation throughout the South Carolina Piedmont region. He also taught former slaves reading and writing and became active in local politics. Some of his congregation would travel as far as 25 or 30 miles twice a month to hear Hill's sermons.

By 1867, Reverend Hill was the president of the York County Union League. He headed the campaign in the South Carolina upcountry to elect former Union Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant as U.S. President in 1868 and was offered a position as a trial justice by the state's Reconstruction Republican Governor Robert K. Scott, which Hill politely declined.

By 1871, Hill regularly held political meetings at his cabin in York County and was a popular preacher working closely with the Union occupation and Captain Williams militia to try and secure the rights of local former slaves.

Unfortunately for both men, their work would meet some of the most fierce opposition in Reconstruction-Era South Carolina as York County would be the site of some of the most intensive white paramilitary violence in the occupied former Confederate States.

James Rufus Bratton was born on Monday, November 12, 1821 in York County. He was one of fourteen children to John Bratton and Harriet Rainey, daughter of James Rainey. His paternal grandfather was Patriot Colonel William Bratton, famous for his victory over Captain Huck during the American Revolutionary War's Southern Campaign in 1780. Bratton was also the first cousin of Confederate Brigadier General John Bratton.

Bratton attended school at Mt. Zion Academy in Winnsboro, South Carolina, and attended the College of South Carolina, where he graduated in 1843. He continued his medical training and in 1845 took a full course in the hospital at the University of Pennsylvania. and graduated from Jefferson Medical College in Pennsylvania. Bratton returned to South Carolina and opened his own practice in York in 1847.

In 1850 Bratton married Rebecca Massey of Lancaster County. The pair had seven children together.

Bratton gained a reputation as a very talented doctor. In a famous case in the mid 1850s, he trephined a skull when the patient suffered great pressure on the brain following a kick by a horse, saving the man's life.

When the War broke out in 1861, he volunteered to be an assistant surgeon for the 5th Regiment, South Carolina Infantry Volunteers under the command of then Colonel Micah Jenkins.

He was then placed in charge of the Fourth Division of the Winder Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, where he served for three years and was promoted to the rank of surgeon. He was transferred to the 20th Regiment of Virginia surgeons under General Braxton Bragg at Milledgeville, Georgia.

After Union General William T. Sherman marched his army through Georgia to Savannah, the hospital was dismantled and Bratton was furloughed and returned to York.

On April 28 & 29, 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was fleeing Union forces through South Carolina and stopped over in York on his way to Georgia. Bratton hosted Davis who spent the night in a guest bedroom.

After the war ended, Bratton largely resumed his medical practice in York, though he was embittered by the South's loss and Reconstruction occupation by Union soldiers. The emancipation of the slaves caused hard times to fall on his family's plantation.

By 1870 Bratton became active in anti-Reconstruction activities and a leader in the York County Ku Klux Klan.

The Ku Klux Klan In York County

The history of the first incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan has its bloody origins from its founding on Sunday December 24, 1865 at the Law Office of Judge Thomas M. Jones in Pulaski, Tennessee by six former Confederate veterans and Masons.

These men conceived the bylaws of the paramilitary group which began as a very cruel joke which began with the men dressing up in horrifying costumes and riding out to scare superstitious African-Americans into believing they were demons, or ghosts.

The group worked as individual cells, largely operating independently of one another, using various violent tactics to frighten and intimidate black Union League members to renounce the Reconstruction government, or intimidate Carpetbaggers and Union supporters from voting in local elections.

When threats didn't work, the members of the Klan would dress up in dark costumes with terrifying masks and enforce their will through incredibly violent and racist means such as whippings and beatings, to burning homes, and finally lynchings.

The KKK organized as early as 1868 in York, and both rich and poor white citizens joined in order to keep blacks from voting and also to disarm black militia companies in the region. By 1871 about 1,800 of the 2,300 adult white males in the county were members of the Klan.

York County became the hotbed of Klan violence and retribution by Union League forces in the winter of 1871.

In an effort to control the escalating violence in the state, Governor Scott officially disbanded the black militia companies in February 1871, but some units -- including William's company -- refused to surrender their arms in order to continue protecting their local communities.

On Saturday, February 11, 1871, Captain Williams, along with June Moore, a nephew of Elias Hill, and a group of Black Union League members met with a group of Klan members led by Bratton at a crossroads near Clay Hill in northern York County to seek to talk about the safety of African-Americans in the area and to deescalate tensions.

Williams suggested that he would be willing to relinquish his militia weapons, and Black Union League leaders agreed to cease nighttime meetings and a brief truce was established.

The truce was broken the next day on Sunday, February 12, 1871 when a race riot broke out involving 500 to 700 whites in neighboring Union County, resulting in the killing eight blacks by Klan members. Ultimately, any further negotiations failed. The black militia would not give up their arms without a fight. This would be followed by nightly Klan raids on black residences in York County for several more months.

|

| Artists depiction of Klan violence (1872). Acts of violence like this became common in the occupied Southern States during the Reconstruction Era. |

Local whites claimed that Williams threatened to kill them and also suggested that his militia was beginning to stockpile weapons. Other slurs included a rumor that Williams said he wanted to rape white women, and also that his militia was responsible for committing arson on a number of white properties.

Similar claims were made against Reverend Elias Hill as well -- which were ridiculous considering the man's disabilities.

Williams, a Union army veteran outspoken in his contempt for the Klan and in his determination to protect the African-American citizens of York County, might well have been responsible for some retaliatory violence in the form of arson of suspected Klansmen's homes. As for the alleged charges that he wanted to "rape white women" these were sensationalist statements meant to demean Williams and to turn people against him and his black militia.

His militia might well have been collecting weapons for self-defense with the growing escalation in Klan violence in the area. However contrast this with his willingness to surrender his militia's weapons in order to establish peaceful coexistence with his white neighbors and the local blacks the month before suggests that Captain Williams was not some dangerous monster, certainly not another Christian Huck.

No matter the validity of the claims made against Jim Williams and the local Black Union League members, there is no doubt whatsoever about what occurred beginning on the night of Monday, March 6, 1871 and the repercussions it would have in our nation's history.

The Lynching Of Jim Williams

It was a full moon that night when a group of about 70 Klansmen gathered at the Briar Patch muster ground about 5 miles west of York.

Led by James Rufus Bratton, the masked and robed men traveled five miles to William’s cabin. As they didn’t know where he lived initially, they beat up Andy Timons, a member of the Union League, in a desperate attempt to find the location of the intended victim.

A few hundred yards from Williams’ house, Bratton brought a smaller detachment of his men to the door. Rose Williams answered, telling them that her husband had gone out and she did not know where he was. The hooded and robed Klansmen crammed into the small cabin. Searching the house, they only found the Williams children and another man. The raiders were not satisfied that their target was gone. Bratton studied the house with his piercing dark eyes and some of the wooden flooring caught his eye.

"He might be under there," the Klan leader said and his men lowered themselves to the floorboards listening for the sounds of any rustling or breathing. Then they tore up the planks. Rose begged for them to stop as they continued to pry up the planks. They found Jim Williams crouched beneath.

Rose pleaded with them not to hurt her husband, but they ordered her to go to the bedroom with her children and marched Williams out of the house.

Andy Timons, meanwhile, scrambled to gather the militia to warn Williams, but the Klan’s head start was too great.

Bratton had brought a rope with him from town and placed it around Williams’ neck as the group selected a pine tree. Williams agreed to climb up by his own power to the branch from which they would drop him, but when they were ready to finish the job he grabbed onto a tree limb.

One of the Klansmen, a man named Bob Caldwell, hacked at Williams’ fingers with a knife until he dropped. Because of his struggling his hanging death was not instantaneous. According to accounts, Williams pleaded and cried, then cursed his murderers as he slowly choked to death. Several of the masked men reportedly fired pistol shots into William's dangling, twitching body.

After the masked men rode off into the night, Timons and Rose found him hanging by the neck with a card on the corpse that mocked the militia leader reading: Jim Williams on his big muster.

Members of William's militia cut down his body and took it to the local store near modern-day Brattonsville and guarded it while sending for the local doctor to preform an inquest. That doctor ironically was James Rufus Bratton himself. In a sick irony, the same man who put the noose around his neck preformed the autopsy of the man he helped murder.

The mob visited several other homes of men involved in the Union League militia, succeeding in gathering 23 guns but no other members. Members of the league swore vengeance, but did not act. In order to prevent any further escalation of violence, Timons reluctantly agreed to turn over the militia company's remaining weapons.

Bratton and the Klan seemingly got their way for now.

The Lynching Of Elias Hill

In spite of the lynching of Captain Williams, Reverend Elias Hill stepped in to lead the now disarrayed Union League.

On the night of Friday, May 5, 1871, a small group of Klansmen burst into the cabin of Hill's brother and demanded to know where the "uppity bastard" Hill resided. They slapped Hill's sister-in-law until she told them Reverend Hill's cabin was just next door.

|

| Solomon Hill & June Moore, nephews of Reverend Elias Hill. Photo taken prior to their immigration to Liberia in October 1871. |

Some of the masked men then went next door and burst into Hill's cabin and dragged him from his bed by straps they wrapped around his feeble neck. Hill was dragged by his crippled arms and legs into the yard and beaten with a horsewhip. He was charged with denouncing the KKK, inciting a riot, and "ravishing white women".

They then threw him onto the muddy ground, beat him, and forced him to admit to starting fires to white-owned properties -- again despite the fact the man was a cripple. Pointing a pistol to his head, they also forced him to renounce support for Republican politics and to swear to publish a statement to that effect in the local newspaper. He was threatened to be thrown in the river and told to stop preaching against the Ku Klux Klan.

His sister-in-law and mother were also beaten the same night. In another raid, Hill's nephews, Solomon Hill and June Moore, were attacked and forced to renounce their Republican Party affiliation in the local paper, the Yorkville Enquirer.

Unlike Captain Williams, Hill survived his encounter with the Klan.

Afraid for his life, and the life of his family, Hill contacted Congressman Alexander S. Wallace and the American Colonization Society, seeking to escape the country.

Hill, along with 135 other African-Americans from the area, boarded the Charlotte, Columbia and Augusta Railroad and traveled to Charlotte, North Carolina, and then to Portsmouth, Virginia. They sailed to Africa on the ship Edith Rose -- a trip that included 243 regular passengers and two stowaways. The group settled in Arthington, Liberia in October 1871.

Reverend Elias Hill died of malaria on March 28, 1872, after only six months in Liberia.

The Aftermath

Klan violence in upstate South Carolina became so intense that drastic measures had to be taken.

Companies B, E, and K of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh U.S. Cavalry led by Major Lewis Merrill soon arrived in the area to try to quell the violence.

Merrill, along with United States Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, traveled to York to investigate incidents of Klan violence. In York County alone they found evidence

of eleven murders and more than 600 whippings, beatings and other aggravated assaults. The men where appalled by their findings and when

local grand juries failed to take action, Mr. Akerman urged now U.S. President

Ulysses S. Grant to intervene.

|

| Colonel Lewis Merrill of Custer's 7th US Cavalry. |

Many affluent Klan members, including Bratton, fled the jurisdiction to avoid arrest, but by December 1871 approximately 600 Klansmen were in jail. Fifty-three pleaded guilty, and five were convicted at trial. Klan terrorism in South Carolina decreased significantly after the arrests and trials, as the Klan could not stand up to intense government intervention.

The Ku Klux Klan formally disbanded a few years before the end of Reconstruction with the organization more-or-less petering out of existence once the Union occupation of the former Confederate States ended in 1876.

Unfortunately the story of the Klan does not end there.

|

| Scene from the film Birth of a Nation depicting a romanticized version of the first Klan routing Black Union League members. |

Dixon's novel was the basis of the 1915 D.W. Griffith silent film The Birth of a Nation, depicting the original Klan in an obscenely romanticized light. This mythological retelling of the Klan's history in turn, would inspire the creation of the second incarnation of the organization, which in turn serves as the basis for the current group by the same name that exists to this day -- though thankfully as a shell of its former self.

Following the end of Reconstruction, nearly all of the formerly occupied Southern States, nor formally restored to the Union, began curbing the freedoms and rights of their black populations, resulting in the Jim Crow laws and racial segregation policies that would largely remain in effect for decades until the passage of the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964 and U.S. Voting Rights Act of 1965 both signed into law by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Doctor James Rufus Bratton returned to South Carolina following Reconstruction and resumed his medical practice. For some period in his life, he was president of the South Carolina State Medical Association.

Bratton died on Thursday, September 2, 1897 and is buried in the graveyard of Historic Bethesda Presbyterian Church near his family, including his grandfather and local Revolutionary War hero Colonel John Bratton. His gravestone only speaks of his noble service as a Civil War surgeon. No mention is made of his Klan activities.

As for Captain Jim Williams, this blogger was unable to locate his grave site. A beautiful mural in downtown Rock Hill, South Carolina depicts him and historical markers at the site speak of his war service and actions during the Reconstruction Era.

Very recently another historical marker honoring his service was installed at the site of Historic Brattonsville near where he grew up in late 2021 -- 150 years after his murder.

Two historical markers at Allison Creek Presbyterian Church near the Carolina state line tell the story of Reverend Elias Hill and the migration of him and his followers to Liberia in October of 1871.

For further reading on the Reconstruction Era in South Carolina, please check out the book Reconstruction: A Concise History by Allen C. Guelzo (Oxford University Press 2018) ISBN:9780190865702.

“In the town of Chester there were stationed two companies of negro soldiers who became very annoying and offensive to the white citizens. At times a bloody riot seemed imminent. On one occasion these black soldiers clubbed and bayoneted an old gentleman, who died from the wounds thus inflicted. Other citizens were at other times injured, and the situation at last became so serious that the obnoxious troops were removed. As they moved out on their train they fired on the citizens, many of whom, fully armed, had assembled at the depot in response to the call that had been previously fixed."

ReplyDeleteSource: RECONSTRUCTION IN SOUTH CAROLINA - 1865-1877. BY JOHN S. REYNOLDS, 1905

"Captain" Williams and his militia were not the angels your making them out to be.

First of all, thank you for the information and for providing a source. I always appreciate any opportunity to share knowledge of local history, even some of the more unpleasant ones. I have another article coming up this month relating to another tragic event (this one more recent) that took place just miles from where I live.

DeleteAs to your other point, I don't believe that I attempted to make out Captain Williams and his militia to be "angels" in any way and I don't see what the quote has to do with them. The companies in Chester were commanded by different people and not Captain Williams in nearby York County.

I'd also like to add that matter what might have been done in York or elsewhere by black militias, the murder of Jim Williams was done by people who gave him no trial, no appeal, and was carried out within yards of his own home in front of his family. Worse it was done by a man, a doctor, who took an oath to help preserve life. There can be no moral justification for that in any society that respects the rule of law.

Again thanks for your review and for your addition to this story.

Thank you so much for standing up for Mr.Williams I received information In my Ancestry that he was my grandfathers great grandfather I’m not sure but I kno his wife Rose was his great grandmother This is so sad to me God rest Their soul

DeleteThanks for this. I'm writing about these events, which involved my family. Can you tell me the source(s) for the dates of Jim Williams's escape and return to York? I've seen conflicting accounts of when he left and have only seen the exact date of his return here in your blog. The interface for your blog does not work in a way I'm familiar with, so I'm posting anonymously, but my name is Dave Lindsay and you can email me at timeandsound@aol.com. Many thanks in advance.

ReplyDeleteYou're probably not going to post this and part of me wonders why I should bother writing at all but here goes. Okay Mr. Roden, Im gonna level with you I never expected this sort of story on this blog from someone like you. From past experiences I assumed you to be the same dangerous neo-confederate propaganda dealer like many others I've dealt with. And yeah you're pretty heavy on the confederate hero worship BS from the posts I've seen here, but I'll give you some points for being more neutral than others. That doesn't mean I buy your motives, or your worship of the "black confederate" myth. I'm just big enough to admit that maybe you might not be a complete lost causer.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for sharing this information Captin James Jim Williams is my Grandfather Bratton Penrose Higginbothams Grandfather

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome.

ReplyDeleteCaptain Williams deserves to have his story told. Its a part of our shared identity, even if the story is a tragic and disgraceful one (the manner of his death, not the man himself). I'm only too happy to share it, lest we forget.

A very good write up thanks for sharing this dark time in our countries history. Growing up nearby it’s unreal how we “white wash” so much of our history, I am a 35 year old white man and just learned about this. The first comment in this post makes you realize how we haven’t gone too far from these racist dark days. The goon is basically minimizing the brutal, disgusting death of Jim Williams because he wasn’t an “angel”. We ALL should truly be embarrassed of this time period in South Carolinas history. However, It’s tough for a lot of us white folks to realize our southern ancestors had a a lot of flaws and did some despicable things. So let’s not learn about those dark days, let’s white wash these times, Truly shameful. We can do better. We clearly have come a long ways in some aspects, but us white folks need to look in the mirror and realize/learn about the darkness of our past. Thanks for sharing this dark moment in history.

ReplyDelete