|

| United Confederate Veterans Reunion, Huntsville, Alabama. Thursday, February 2, 1928. (Photo courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives) |

Busting The Myth Of Black Confederate Denial

The Common Sense Defense of Confederate Veterans of Color

By C.W. Roden

Dedicated to the honored memory of

those Confederate Veterans of color

unable to speak for themselves.

This writer is proud to offer his voice in defense

of their memory and their everlasting valor.

those Confederate Veterans of color

unable to speak for themselves.

This writer is proud to offer his voice in defense

of their memory and their everlasting valor.

In my quarter of a century involved in Confederate heritage defense, this writer has had the privilege of meeting various descendants of Confederate veterans from all walks of life. All of them (men, women, and children alike) share with me the honor of being the descendants of the Southern citizen soldier -- both the honored dead who fell during the War Between the States (1861-1865) and those who lived on during the Reconstruction Era and beyond as United Confederate Veterans.

As a Southern-born man and proud Confederate descendant, I'm proud to be counted among those who share that unique pride in our common Confederate ancestry, my Southern brothers and sisters who share that same honorable and unique heritage that make us all children of Dixie. It is that Southern heritage that binds us beyond social class, religious creed, and yes, especially skin color.

To me there is no difference between a Southern-born African-American like Private Henry "Dad" Brown who served as a drummer, or a 19 year old Southerner of Anglo-Celtic descent like Sergeant Richard Kirkland, or a large plantation owner and Confederate general like Wade Hampton III -- or for that matter my own Confederate ancestor, an Alabama farmer who fell in battle at Chickamauga during the course of the War. All of them wore the same uniform, fought under the same Confederate battle flag (or some variation of it), and all of them were defenders of Southern independence. None of them are worth any more, or any less than the other in my eyes; and neither are those proud descendants of any of those same Confederate veterans.

During the course of defending our shared Southern-Confederate historical heritage, it has been my deep personal honor to meet with descendants of many Confederate Veterans of color (a few of them Real Daughters and Real Grandsons) who'd actually known their ancestor personally. As a student of history I've listened to the amazing personal stories of their Confederate ancestors with great interest. I've also found many of these people to be outstanding folks and treated with the highest respect by other proud Confederate descendants.

Like other stories of African-American courage and excellence in American history, these particular Confederate veterans -- these American veterans -- have been overlooked by the wider American public, and the largely whitewashed general American historical record for far too long.

Thankfully, in the decades following the American Civil Rights Movement, efforts to tell the full account of African-American roles in the forging of our overall American national identity have advanced considerably. As a member of Generation X growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, and a student of history, I've also been privileged to learn about much of that history -- the good and the bad -- as it came to light; especially those stories of Confederate Veterans of color, among other amazing personal stories of black excellence in Southern and American history.

It is because of this profound respect for Southern and American history and our shared Confederate heritage that I hold a particular disdain and personal moral disgust for those white supremacists and self-proclaimed "Social Justice Warriors" who mock the service of these veterans through the thinly-veiled form of regressive bigotry known as Black Confederate Denial.

Today, this writer is going to present the facts and common sense logic on the subject of Black Confederates, as well as present the ultimate failure of the Black Confederate Denial narrative.

Anyone expecting what may best be described as "neo-Confederate propaganda" will find themselves disappointed. Too many amateur mistakes and untruths have already been spoken about the service of the Black Confederate veteran -- not much unlike the many myths surrounding the War itself on both side of the argument.

This author will present nothing but the plain facts and any speculation by the writer will likewise be noted. Certainly I will present my very typical pro-Southern opinion, but will refrain from writing any unverified information including guess work (unless noted) and purposeful mistruths about any specific individual, or group. To do so would diminish the honor of not only these Confederates of Color, but of every Confederate Veteran who served in the defense of their Southern homeland.

The only agenda here is to explain the service of these people, and I will leave it to you, the reader, to determine for yourself if the common sense case has been made for these Confederates of Color.

Black Confederate Denial & Its Sinister Implications

Black Confederate Denial can be best defined as an obscene form of historical negationism and that promotes the dehumanization of the Black Confederate Veteran. It is an attempt to negate the established facts of the service of Southern men of color.

Black Confederate denial and distortion are forms of racial bigotry at their core. They are generally motivated by personal hatred of the memory and identities of African-Americans -- both living and dead -- that reject the established narrative that black Americans were only loyal to the Union. These acts largely serve to undermine the understanding of the complexities of American history.

In the last decade, a small but somewhat vocal group of largely "politically correct" agenda-driven historians in the American academic community have challenged the legitimacy of these Southern men of color. Their arguments are largely based on little more than accusations as to the alleged motives of the modern-day Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy in honoring them. Both the memory of Black Confederates and their proud descendants have come under attack from this vocal group of dubious academics who strongly advocate the Righteous Cause Mythology.

The methodology of these views also hold uncomfortable similarities with Holocaust Denial in the way these same agenda-based academics present history. Black Confederate Denial is historical gaslighting at its worst, largely built on a house of cards made up of half-truths and defended by illegitimate strawman arguments.

In this case Deniers start their arguments by presenting a couple of true historical facts such as the historically true detail that the Confederate government did not formally enroll black Southerners into the Confederate army until March of 1865, and only reluctantly after serious debate.

While the detail itself is true, it does not accurately present the full story of the Black Confederate loyalist as an individual, or his experience. But instead of dealing with these men as individuals, the group-think mentality largely associated with Left-wing identity politics comes largely into play here. Rather than confront an individual story that contradicts the narrative, the Denier chooses to ignore the story and repeat their original talking points ad nauseam.

Another favorite argument of Black Confederate Deniers is to say that black men who preformed service jobs were not legally soldiers since many Black Confederates present in Confederate units were not formally enrolled as soldiers on the unit's muster rolls themselves. These Deniers also largely reject the service of free men of color in Confederate service ranks, focusing instead of those slaves and declaring their service invalid since slaves had no free will and therefore no choice. This one is called the "slaves not soldiers" argument, in effect saying that these men were "non-people" in much the same way that a Leftists groups today regard non-white social conservatives as "race traitors" and dehumanize them socially through terrible forms of internalized bigotry.

Worse, Black Confederate Deniers insist that their reasons for doing so are about preserving the integrity of the historical record while at the same time using that as a cover to attack the descendants of these Confederate veterans themselves -- the true targets of these mean spirited and hateful people.

Can

you imagine anything more hurtful and demeaning than having some

triggered academic with a chip of their shoulder saying to someone

that their ancestor was "just a ditch digger" and not a soldier? That

they did not deserve the dignity of being remembered as anything more

than a "slave" regardless if the charge is true?

These

reasons alone would be more than enough for this writer to actively speak out against this sort of

backdoor bigotry disguised as academia, though an even more sinister reason also exists.

Black Confederate Denial talking points are also largely quoted by extreme Alt-Right white nationalists, many of them active members of white supremacist organizations who oppose the idea of honoring Confederate Veterans of Color, or promoting what they erroneously term the "Rainbow Confederacy" -- a term that is also popular among Deniers themselves.

In point of fact, there is an uncomfortably close informal alliance between these historical negationists and white racists to undermine the memories of these men, each for their own sordid goals. A sort of alliance between useful idiots one can say.

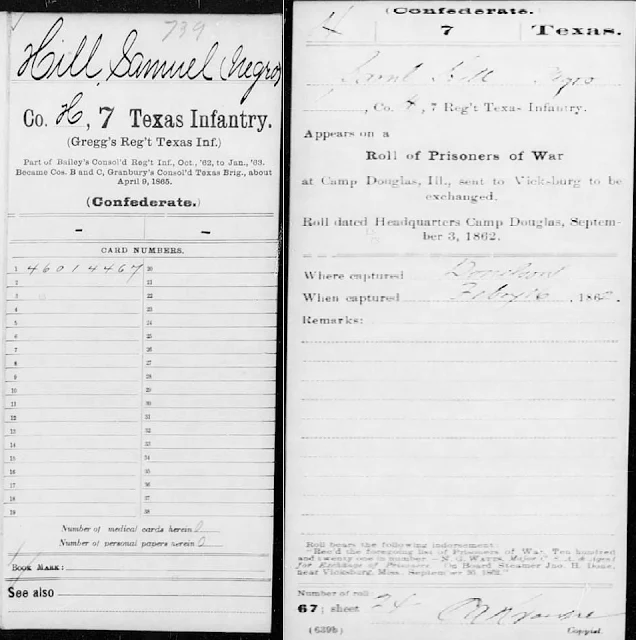

Ultimately the arguments of Black Confederate Deniers do not hold up well when subjected to even the most unbiased scrutiny. When those arguments are challenged, almost all of these Deniers throw up strawman arguments to counter the holes in their chain of logic. They will demand proof of service. When service records or muster rolls are provided, the Deniers cry foul, declare the evidence invalid for whatever reason and then retreat to the same tired and used up talking points, and then declared victory over their opponents. All the while justifying their obscene and dehumanizing actions as efforts to promote "real" Black History and experience.

The following rant taken from the social media site facebook and written by one of the more vocal proponents of Black Confederate Denial historical negationism (an individual whose name I will not post here) is typical of their arguments and how they denigrate the memory of a Confederate of Color -- while at the same time pretending to honor them service and experience of African-Americans loyal to the Union:

Black Confederate Denial talking points are also largely quoted by extreme Alt-Right white nationalists, many of them active members of white supremacist organizations who oppose the idea of honoring Confederate Veterans of Color, or promoting what they erroneously term the "Rainbow Confederacy" -- a term that is also popular among Deniers themselves.

In point of fact, there is an uncomfortably close informal alliance between these historical negationists and white racists to undermine the memories of these men, each for their own sordid goals. A sort of alliance between useful idiots one can say.

Ultimately the arguments of Black Confederate Deniers do not hold up well when subjected to even the most unbiased scrutiny. When those arguments are challenged, almost all of these Deniers throw up strawman arguments to counter the holes in their chain of logic. They will demand proof of service. When service records or muster rolls are provided, the Deniers cry foul, declare the evidence invalid for whatever reason and then retreat to the same tired and used up talking points, and then declared victory over their opponents. All the while justifying their obscene and dehumanizing actions as efforts to promote "real" Black History and experience.

The following rant taken from the social media site facebook and written by one of the more vocal proponents of Black Confederate Denial historical negationism (an individual whose name I will not post here) is typical of their arguments and how they denigrate the memory of a Confederate of Color -- while at the same time pretending to honor them service and experience of African-Americans loyal to the Union:

In its essence, the whole fixation with "black Confederates"

reflects a desperate attempt to seek cover from the massive onslaught of

facts that establish the decisive role of African Americans in securing the victory of the United States over the slaveholders' rebellion.

200,000 black men, the great majority former slaves, served as soldiers

in the United States Army. A similar number served in every

noncombatant role in that army. Their dependents comprised another half

million or more men, women, and children, most of whom also served by

working either directly for the government (e.g., on lands administered

by the Treasury Department) or in the civilian workforce. That transfer of labor alone would have destroyed the Confederacy, but its reformation into direct military and labor support for the other side, the side of freedom, hurried the rebellion's demise to the benefit of all of us today. And that transfer of labor occurred without the initial support (and sometimes in the face of opposition from) the U. S. government, and despite slaveholders' violence (including forced removals and outright murder), the conditions in ill-prepared "contraband" camps, widespread illness, and general racism.

In all this, African Americans showed all the greatest qualities we like to associate with the American character: initiative, courage, family values, and love of freedom. And yet there remain today innumerable white Americans who cannot process that great truth. Instead they embrace a mythology founded on the enforced services of the enslaved, the entrapped, the racially ambiguous, and trace minority of people of color employed by a government founded on a cruel racist ideology. Nothing else explains why white people spend so much time on this unicorn hunt while knowing little and caring less about the reality of the USCT and contraband experience.

Some of you all really need to step back, take a look at the big picture, and come to grips with why your perspective has little sway with serious historians. And we all could benefit from focusing more on the experiences of the USCT and contrabands who saved our great country in its hour of greatest need.

This writer would like to offer a small point of correction: the official numbers for the United States Colored Troops is listed at approximately 178,600 men and boys in 175 individual units, but then again the individual who wrote that rather long and boring piece made far more than just one factual error.

Now let me show you where this individual, and others like them, get it wrong.

Defining The Black Confederate

The term "Black Confederate" is a largely general term that has come to describe any Southern-born African-American who has been said to have served in some capacity within the Confederacy during the period of the War Between The States.

It must also be admitted by this writer that some well-meaning people who defend the memory of the Confederate soldier have, at times, inadvertently offered validity to Black Confederate Denial through largely ridiculous and inflated claims about Black Confederate Veterans and their service. Mostly through a combination of exaggerating the number of Black Confederates who served and not clearly defining the difference between someone who preforms the duty of a soldier, or as a citizen who acts out of patriotic duty.

Why would a black man serve with and fight for a Confederate government that, if successful in establishing their independence, would almost certainly have resulted in the continued enslavement of many of these men, as well as a large majority of their fellow Southerners of color, including possibly their own families?

Were these men actually slaves without free will forced into Confederate service with rifle barrels put to their heads as Deniers claim? Were they willing Southern patriots, like white Southern men fighting of their own free will to defend their Southern homeland from invasion? Were they both and neither at the same time? How many of them served and do they deserve the designation "soldier" by either 19th or 21st century standards?

The answers to these questions is not always so black and white and shows the complex nature of the relationship between the two main ethnic groups of the American Southland.

The main problem with the broad term is that it implies that every African-American who had any sort of service in the Confederate military was a Black Confederate, or held loyalty to the Confederacy. Stories regarding such black men in Confederate service going over to the Union side when the occasions offered argues strongly that this was not always the case.

The most well known and documented example of this is the defection of Robert Smalls, a African-American slave of mixed ethnicity who served as a pilot for the Confederate transport steamer CSS Planter. Smalls defected to the Union blockade fleet surrounding Charleston harbor along with a crew of other black Southern slaves and their families.

Now add the word "soldier" at the end of Black Confederate and this raises even more eyebrows.

Most cases of the service of black Southerners involved manual labor on fortifications around major cities, transportation of supplies, the making of war materials, and service as nurses and stewards in Southern military hospitals. To imply these individuals as a whole served in a field capacity as Confederate soldiers is likewise a broad stretch, though one easily made by some well meaning folks in the Southern Heritage Defense community. By no means does this diminish the important work done by these people on behalf of the Confederate war effort, but in and of itself does not suggest that all of these people were Southern loyalists.

So what is the proper definition of a Black Confederate?

These are the three best examples of how one can best define a Black Confederate:

(1) Any black male, slave or freeman, who served in the Confederate military in any service capacity (cook, musician, teamster, body servant, or other such service job) who, of his own free will and without coercion, fought in defense of an individual Confederate soldier, a Confederate unit, or acted in defiance against the Union military.

(2) Any black male, slaver or freeman, who served in the Confederate military in any service capacity captured by Union forces, imprisoned in Union prisoner of war camps, and refused despite all efforts by the enemy to take the oath of loyalty, desert, or behave in any way disloyal to the Confederate military, or the Confederacy.

(3) Any black Southern civilian who, of their own free will, volunteered their service, or preformed any action in support of, or in defense of, the Confederacy against the Union invader.

Black Confederate Loyalty

Deniers will loudly insist that no black Southerner was truly loyal to the Confederate cause of independence. They state the obvious reason being that the Confederacy was founded on the cornerstone of racial inequality and the establishment of a "slavocracy" in North America.

The argument over whether African-Americans took up arms to fight for a government that enslaved them is a bitter one. Throw in the usual "social justice" balderdash and this leads to some really intense arguments, to say the least.

As I pointed earlier, Black Confederate Denial begins with pointing out at least some historically relevant truth as a foundation.

The very first card in the Denier's house of cards is the argument that Confederate policy did not allow slaves to be soldiers until March of 1865, and even then only on limited terms. Of all their arguments, this one is the only one that holds a kernel of actual historical truth to it.

In January of 1864, Confederate Major General Patrick R. Cleburne and several other Confederate officers in the Army of the Tennessee proposed the formal enlistment of slaves as Confederate soldiers. The proposal was largely met with disdain by some in the Confederate Congress and by President Jefferson Davis himself. With the war beginning to wind down late in 1864, the Confederate Congress finally took up a very bitter debate on allowing the creation of Confederate regiments of colored troops, as the Union had established with the creation of the United States Colored Troops. On Wednesday, January 11, 1865 General Robert E. Lee himself wrote the Confederate Congress urging them to arm and enlist black slaves in exchange for their freedom. This did not finally happen until Monday, March 13, 1865 -- less than a month before the fall of Richmond, Virginia and the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia.

None of these facts are in dispute by anyone on either side of the argument, and even the most ardent Confederate heritage defender will concede the points made. Certainly this writer does not dispute these historical facts.

Right now I can hear the whoops and cheers of Deniers as they jump up and down shouting in victory at my concession.

Yeah, not so fast there.

The argument over the formal enlistment of slaves was largely made over the idea of making whole Confederate regiments out of slaves.

Most Black Confederates who served in the ranks of the Confederate army did so as individuals as part of larger units of already established Confederate regiments on the field. How many of these individuals served in each regiment would largely depend on a number of factors, including what their particular service was in terms of their service job. However, we will get into the debate over the actual number later on.

While it is true that legally a slave could not be a soldier in terms of specific Confederate government policy, this did not stop a significant number of black Southern loyalists, many of them free men of color, from volunteering their services to their local Confederate regiments to preform whatever job could legally be required by them.

Here comes the first laughable Denier strawman folks: "But there weren't any free black men in the Confederacy!"

Actually that is far from true according to the US Census data taken in 1860. There were over 250,000 free African-Americans in the States that would make up the Confederacy, and border states that were largely divided in their loyalty between the North and South.

Obviously support for the Confederacy among the free black population was mixed, just as it was for a large part of the Southern States. Secession and independence was not universally accepted in the South, and, for that matter, a war to restore the Union was not completely popular with some parts of the North either. When we say War Between the States, we usually just mean the governments of said States as opposed to some of the populations of those same States.

Loyalty to community and home were a large factor for many Black Confederates, as it was for the rest of the people in the South. Many people living back in 1860, particularly poor people, knew only the small communities they grew up in. Some folks never traveled more than a couple days walking distance from their homes for most of their lives. Their families were there, either living their lives, or buried in local cemeteries. Some of them several generations that laid their roots there.

Defending those homes, those communities, and those family bonds were the driving factors for young Southern men to join their local regiments and march off. The martial sense of personal duty most Americans believed in at the time was also a factor -- not to mention the opportunity to see more of the world and get away from their mundane jobs, or chores, for a time.

|

| Members of the 2nd SC Regiment camped at Stono Inlet, near Charleston, SC. in 1861. (Photo courtesy of the SC Department of Archives) |

In a Civil War regiment there was no place for idle hands or lazy people. Many of these Black Confederates attached themselves to a group of soldiers to help with the duties of camp life -- of which there was quite a few, and an extra pair of hands were always welcome for the common foot soldier.

Unlike some of the slaves who were brought with their masters, and likely didn't choose to come to war willingly, many free men of color hired themselves out to officers as their servants, or volunteered to serve in the ranks at these various service jobs.

During battles, many of these personal servants and service people would sometimes preform acts of great personal courage. For instance there are many personal accounts recorded of body servants going out into the fields during and after battles looking for their fallen masters -- either looking for a wounded man, or a body. A number of these black slaves would return the body home to family, then return and offer their services back to the unit they were serving with. Often times they stayed with their group and preformed whatever service was required of them until the end of the War.

On many occasions throughout the four years of the War, many of these Black Southern men, in preforming the usual duties of camp life, were on many occasions entrusted by those white Confederate soldiers they both served and served with, to preform extra-ordinary services such as foraging for food supplies, guarding prisoners, and even standing armed sentry post along the front lines.

One such case is that of one Mr. Alex Sarter of Union County, South Carolina. Sarter served in the Army of Northern Virginia first as a slave, and then later as a free man of color. William Sarter, his original owner, was appointed captain in Company B, 18th SC Infantry Regiment on August 1862. Captain Sarter later died the following September from his war wounds, but Alex chose to stay on with the 18th SC after William died, and was often trusted with picket duty. He would be captured during the siege of Petersburg in 1864 and later escape Union custody. He survived the war and is listed among the rolls of the United Confederate Veterans.

In many instances some of these Black Confederates would pick up a fallen weapon and join the men they served with in the front line ranks, fighting for the defense of Dixie no different than any other Confederate soldier. Many of these acts were documented in personal diaries, and on occasions in newspaper accounts of the time detailing some extraordinary acts of courage.

One very good example of this is a small article posted in the New Orleans Daily Crescent on Friday, December 6, 1861 which reads:

"It would be impossible to give an account of all the acts of personal

valor which took place in the fight; but I cannot omit to mention that Levin

Graham, a free colored man, who was employed as a fifer, and attendant to Capt.

(J. Welby) Armstrong (Co. G., 2nd Tennessee), refused to stay in camp when the

regiment moved, and obtaining a musket and cartridges, went across the river

with us.

"He fought manfully, and it is known that he killed four of the Yankees, from one of whom he took a Colt's revolver. He fought through the whole battle, and not a single man in our whole army fought better."

Black Confederate soldiers?

Now this is where Black Confederate Deniers and their white supremacists allies collectively feel they have the greatest advantage in their dehumanizing arguments against the service and humanity of Black Confederates.

If Confederate government policy on arming African-American slaves as soldiers is the first card in the Denier house of cards, then the card that props it up is the argument that individual slaves cannot be soldiers because of this policy. In fact virtually every Denier to a person will gleefully point this detail out in every single argument they make on the subject.

"He fought manfully, and it is known that he killed four of the Yankees, from one of whom he took a Colt's revolver. He fought through the whole battle, and not a single man in our whole army fought better."

Black Confederate soldiers?

Now this is where Black Confederate Deniers and their white supremacists allies collectively feel they have the greatest advantage in their dehumanizing arguments against the service and humanity of Black Confederates.

If Confederate government policy on arming African-American slaves as soldiers is the first card in the Denier house of cards, then the card that props it up is the argument that individual slaves cannot be soldiers because of this policy. In fact virtually every Denier to a person will gleefully point this detail out in every single argument they make on the subject.

This one is what this writer previously referred to as the "slaves not soldiers" argument. This argument erroneously claims that all African-Americans in the Confederate ranks were not legally soldiers and their service was the work of slaves with no minds and no thoughts of their own, coerced there by white masters against their free will.

The first point in this fact, which has been demonstrated here, is that many Black Confederates were in fact free men of color, rather than slaves. Whenever confronted with this detail, the Denier usually argues that such men were few and far between, or they throw up another little strawman argument: Confederate policy says that, before March 1865, African-Americans could not be Confederate soldiers; therefore legally they are not soldiers.

Yes for the most part the Confederate Government as a federal entity prohibited the enlistment of African Americans -- especially slaves -- as armed soldiers in the Confederate army. As I stated before, this is an undeniable historical fact backed up a figurative mountain of evidence in just about every American historical text.

However, pay attention to the keywords "national army" in discussing official Confederate policy regarding Black Confederates. This is a really important point.

Unlike the United States government, with its strong central government -- one that became much stronger as a result of the War, the Confederate States government was a coalition of Southern States, each with their own sovereign State governments. The Confederate national government itself was far weaker in terms of how the Confederate Constitution defined federal power by design.

The Southern States themselves still controlled their own military policies within the Confederate command structure but, unlike the Union, did not entirely surrender total control of their forces as part of a "national army." In many ways this was much like how the original Continental Army was structured during the American Revolutionary War prior to the later ratification of the US Constitution in 1787.

As a result the various Confederate States and individual units often varied from, or ignored outright, many such prohibitions since there were actually very few "national army" regiments at any time during the war with most military units still under state command on loan to the Confederate government.

Some individual Confederate States permitted free blacks to formally enlist in their state militias.

One of the first to do so was the State of Tennessee which passed a law on Friday, June 28, 1861 authorizing the recruitment of state militia units composed of free persons of color between the ages of 15 and 50. The first three provisions of this act read as follows:

Sec. 1. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Tennessee, That from and after the passage of this act the Governor shall be, and he is hereby, authorized, at his discretion, to receive into the military service of the State all male free persons of color between the ages of fifteen (15) and fifty (50) -- or such numbers as may be necessary, who may be sound in mind and body, and capable of actual service.

Sec. 2. Be it further enacted, That all such free persons of color shall be required to so all such menial service for the relief of the volunteers as is incident to camp life, and necessary to the efficiency of the service, as of which they are capable of performing.

Sec. 3. Be it further enacted, That such free persons of color shall receive, each, eight dollars per month, as pay, and such persons shall be entitled to draw, each, one ration per day, and shall be entitled to a yearly allowance each for clothing.

W. C. WHITTHOUNE, Speaker of the House, of Representatives. B. L. STOVALL, Speaker of the Senate.

Passed June 28, 1861.

*Source: Public Acts of the State of Tennessee Passed at the Extra Session of the Thirty-Third General Assembly. April 1861. AN ACT for the relief of Volunteers. Chapter 24 [Pg 49-50].

The State of Louisiana, which had a sizable free black population (see graph table above), followed suit and assembled the all-black 1st Louisiana Native Guard. This regiment was later forced to disband in February, 1862 when the state legislature passed a law in January, 1862, that reorganized the militia by conscripting “all the free white males capable of bearing arms… irrespective of nationality”.

It should be noted that the 1st LA Native Guard did not see any real combat in Confederate service, though many members did re-enlist when the Union occupation of New Orleans took over in 1862 and was reformed as a Yankee regiment.

The State of Alabama authorized the enlistment of "mixed blood" (mulatto) Creoles in 1862 for a State militia unit in Mobile. Some Black Confederates were of mixed ethnicity and some could pass as white men and joined regular State regiments as private soldiers.

At least one Black Confederate was a non-commissioned officer. 3rd Sergeant James Washington of Co. D, 35th Texas Cavalry.

Now the Deniers start screaming, These men where not official soldiers! It's all about official Confederate government policy stupid!

Not according to the accepted literature of the time. In fact, in American military history, the definition of soldier is not entirely restricted to those who were formally enlisted.

The following is an excerpt from the Customs of Service For Non-Commissioned Officers and Enlisted Men written by Union General August V. Kautz (and take special note of what it says about musicians, this will shortly be important):

THE PRIVATE SOLDIER.

IN the fullest sense, any man in the military service who receives

pay, whether sworn in or not, is a soldier, because he is subject to military

law. Under this general head, laborers, teamsters, sutlers, chaplains, &c. are

soldiers. In a more limited sense, a private soldier is a man enlisted in the

military service to serve in the cavalry, artillery, or infantry. He is said to

be enlisted when he has been examined, his duties of obedience explained to him,

and after he has taken the prescribed oath.

“Any free white [*] male person above the age of eighteen, and under thirty-five years of age, being

at least five feet three inches high; effective, able-bodied, sober, free from

disease, of good character and habits, and with a competent knowledge of the

English language, may be enlisted as a soldier” (Reg. 929.) This regulation

makes exceptions in favor of musicians and soldiers who have served one

enlistment, although they should be under the prescribed height and age. A

soldier cannot claim a discharge in consequence of any defect in the above

requirements, unless, in case of a minor, he can prove that the requirements of

the law have not been complied with in his enlistment.

[*] The enlistment of Negroes and Indians is a peculiarity of the volunteer service, and has not yet been authorized for the regular service.

Furthermore, despite Denier claims that the Confederate government did not approve of Black Confederate service, it might surprise the reader that the Confederate Congress did in fact officially recognize the service of those African-Americans preforming their jobs in Confederate regiments....and passed two laws authorizing equal payment for those services!

The following are military rules approved by the Confederate Congress in regards to Black Confederates.

Chapter XXIX. - AN ACT for the payment of musicians in the Army not regularly enlisted.

The Congress of the Confederate States of America do enact, That whenever colored persons are employed as musicians in any regiment or company, they shall be entitled to the same pay now allowed by law to musicians regularly enlisted: Provided, That no such persons shall be so employed except by the consent of the commanding officer of the brigade to which said regiments or companies may belong.

Approved April 15, 1862.

Chapter LXIV. - A BILL [AN ACT] for the enlistment of cooks in the Army.

The Congress of the Confederate Slates of America do enact, That hereafter it shall be [the] duty of the captain or commanding officer of his company to enlist four cooks for the use of his company, whose duty it shall be to cook for such company--taking charge of the supplies, utensils and other things furnished therefor, and safely keep the same, subject to such rules and regulations as may be prescribed by the War Department or the colonel of the regiment to which such company may be attached:

[SEC. 2.] Be it further enacted, That the cooks so directed to be enlisted, may be white or black, free or slave persons: Provided, however, That no slave shall be so enlisted, without the written consent of his owner. And such cooks shall be enlisted as such only, and put on the muster-roll and paid at the time and place the company may or shall be paid off, $20 per month to the chief or head cook, and $15 per month for each of the assistant cooks, together with the same allowance for clothing, or the same commutation therefor that may be allowed to the rank and file of the company.

Approved April 21, 1862.

*Source: Public Laws of the Confederate States of America Passed at the First Session of the First Congress 1862 (Pages. 29 & 48).

It would be here that the Denier would jumped out of their seat to scream: Musicians are NOT soldiers!

In point of fact they were according to the official Confederate military policy. In fact here are a couple of rather interesting excerpt from the Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States 1863:

75. The musicians of the band will, for the time being, be dropped from company muster-rolls, but they will be instructed as soldiers, and liable to serve in the ranks on any occasion. They will be mustered in a separate squad under the chief musician, with the non-commissioned staff, and be included in the aggregate in all regimental returns.

1400. No person under the age of twenty-one years is to be enlisted without the written consent of his parent, guardian, or master. The recruiting officers must be very particular in ascertaining the true age of the recruit, and will not accept him when there is a doubt of his being of age.

*Source: Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States 1863 (Pages 13 & 178).

There is no doubt that musicians faced bullets and cannon shots, especially the regiment's drummers who accompanied the regiments onto the battlefield. There are literally a hundred individual accounts of drummers on both sides of the War who were wounded in battle -- the most famous account is probably the Union soldier Johnny Clem, the Drummer Boy of Shiloh and Chickamauga.

Wagon drivers were certainly subject to the dangers of battle, particularly the men delivering ammunition, or driving the teams that carried the artillery to the field. Stretcher bearers and men who drove the hospital wagons, many of them also Black Confederates, were also subject to stray bullets from the enemy -- sometimes deliberate fire by enemy snipers.

How does a Denier respond to this information? Well, usually with a lot of stammering, or more often with the sound of their deafening silence.

Official Records Of Black Confederate Service

Many of the muster rolls of various Confederate units list Black Confederates under military rank in addition to their service rolls. Keep in mind that this is not always a constant with every Confederate unit and regiment -- again that variation between the standards set for each State's troops -- but it is clear from such evidence that these men were considered an integral part of the unit itself. It also shows that many of these men were not in fact all slaves, but free men of color. This further shows that the "slaves not soldiers" arguments so often purported by Deniers to be a falsehood.

There were many recorded instances of combat service of Black Confederates which can be found in the Federal Official Records, Northern and Southern newspapers and the letters and diaries of soldiers from both sides. In addition there are recorded instances of Black Southerners serving as regularly-enlisted combat soldiers before the Union allowed enlistment of African-Americans.

The following passages are from The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War.

Federal Official Records, Series I, Vol XVI Part I, pg. 805, Lt. Col. Parkhurst's Report (Ninth Michigan Infantry) on General Forrest's attack at Murfreesboro, Tenn, July 13, 1862:

"The forces attacking my camp were the First Regiment Texas Rangers [8th Texas Cavalry, Terry's Texas Rangers, ed.], Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers, Colonel Morrison, and a large number of citizens of Rutherford County, many of whom had recently taken the oath of allegiance to the United States Government. There were also many negroes attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day."

Union officials and even those in the US Government itself were fully aware of the existence of Black Confederates.

Federal Official Records, Correspondence, Etc., Vol. II, pg. 218 -

"...they [the Confederacy] have, by means of sweeping conscription, gathered in countless hordes, and threaten to overwhelm the armies of the Union, with blood and treason in their hearts. They flaunt the black flag of rebellion in the face of the Government, and threaten to butcher our brave and loyal armies with foreign bayonets. They arm negroes and merciless savages in their behalf."

- July 11, 1862 - Rich D. Yates, Governor of Illinois to President Abraham Lincoln.

Perhaps the most telling of such accounts from a Union source detailing the service of Black Confederates in Southern ranks comes from the official report of Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, Inspector of the US Sanitary Commission.

Steiner was present in the town of Frederick, Maryland on Wednesday, September 10, 1862 when the Army of Northern Virginia passed through in their first invasion of the North. He watched the Confederate army pass from the second story window of a hotel.

It should be noted that as a pro-Unionist, Dr. Steiner did not paint the Confederate army in a particularly positive light in his report. He takes great pains to point out outrage and outrage -- true or otherwise -- that the Confederates allegedly did when they marched through town. His description of the presence of African-Americans in the Confederate ranks is therefore not meant to be a complement, rather an example of racial prejudice. For Steiner, the presence of Black Southerners in the ranks just serves as another moral outrage to be condemned and presents their presence as such. Yet despite his clear prejudices, Dr. Steiner's accounts offer a very eye-opening pair of statements on the presence of Black Confederates.

Here is the first, on pages 19-20 of the report:

"Wednesday, September 10. -- At four o'clock this morning the rebel army began to move from our town, Jackson's force taking the advance. The movement continued until eight o'clock P.M., occupying 16 hours. The most liberal calculations could not give them more than 64,000 men.

Over 3,000 negroes must be included in this number. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, ect. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabres, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied, in many instances, with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc., and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederacy Army. They were seen riding on horses and mules, driving wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances, with the staff of Generals, and promiscuously mixed up with all the rebel horde. The fact was patent, and rather interesting when considered in connection with the horror rebels express at the suggestion of black soldier being employed for National defense."

From that point on, Steiner offers some less than flattering comments about the state of the Confederate army, and then on page 21 of his report, he offers yet another interesting comment regarding African-Americans in the Confederate ranks:

"Their apologies for regimental bands were vile and excruciating. The only real music in the column to-day was from a bugle blown by a negro. Drummers and fifers of the same color abounded in their ranks."

The following story about Black Confederates on picket duty near Fredericksburg, Virginia appeared in New York's Harper's Weekly newspaper dated Saturday, January 10, 1863:

REBEL NEGRO PICKETS

So

much has been said about the wickedness of using the negroes on our side in the

present war, that we have thought it worthwhile to reproduce on this page a

sketch sent us from Fredricksburg by our artist, Mr. Theodore R. Davis, which

is a faithful representation of what was seen by one of our officers through

his field-glass, while on outpost duty at that place. As the picture shows, it

represents two full-blooded negroes, fully armed, and serving as pickets in the

rebel army. It has long been known to military men that the insurgents affect

no scruples about the employment of their slaves in any capacity in which they

may be found useful. Yet there are people here in the North who affect the be

horrified at the enrollment of negroes into regiments. Let us hope that the

President will not be deterred by and squeamish scruples of the kind from

garrisoning the Southern forts which fighting men of any color that can be obtained.

Deniers would argue that both the Steiner report and the account in Harper's Weekly is just propaganda used to promote the idea for enlisting African-Americans for the United States Colored Troops -- which was really not a popular idea in the Northern States in late 1862 and through much of 1863. If the Rebels were doing it, then why not the national army? Yet this would not account for the many official Federal reports that expressly state that Union soldiers encountered armed Black Confederates in battle.

Here the ever desperate Deniers start sweating and begin to flat out deny the official historical records, and they shout: The reports are not accurate! Battle accounts are not real evidence! After that they tend to refer back to the previous strawman arguments that Black Confederates cannot be soldiers because of official government policies -- which have just been demonstrated to be failed arguments.

Now if the verified testimony of Union sources is not enough, how about a source from a more neutral witness?

During the summer of 1863, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Arthur James Lyon Fremantle of the British Army traveled with Lee's Army into Pennsylvania and was present during the Gettysburg Campaign. His observations as an unofficial military observer were published later on and include the following amusing story and personal observation:

I saw a most laughable spectacle this afternoon-viz., a negro dressed in full Yankee uniform, with a rifle at full cock, leading along a barefooted white man, with whom he had evidently changed clothes. General Longstreet stopped the pair, and asked the black man what it meant. He replied, "The two soldiers in charge of this here Yank have got drunk, so for fear he should escape I have took care of him, and brought him through that little town." The consequential manner of the negro, and the supreme contempt with which he spoke to his prisoner, were most amusing. This little episode of a Southern slave leading a white Yankee soldier through a Northern village, alone and of his own accord, would not have been gratifying to an abolitionist. Nor would the sympathizers both in England and in the North feel encouraged if they could hear the language of detestation and contempt with which the numerous negroes with the Southern armies speak of their liberators.*

* From what I have seen of the Southern negroes, I am of opinion that the Confederates could, if they chose, convert a great number into soldiers; and from the affection which undoubtedly exists as a general rule between the slaves and their masters, I think that they would prove more efficient than black troops under any other circumstances. But I do not imagine that such an experiment will be tried, except as a very last resort, partly on account of the great value of the negroes, and partly because the Southerners consider it improper to introduce such an element on a large scale into civilized warfare. Any person who has seen negro features convulsed with rage, may form a slight estimate of what the result would be of arming a vast number of blacks, rousing their passions, and then allowing them free scope.

*Source: Three Months In The Southern States (April - June 1863) By Col. Fremantle (Pg. 141-142)

As Sir Arthur pointed out from the story and his personal observation, individual Black Confederates showed considerable loyalty to the units they served with. He also pointed out that the Confederacy could have utilized slaves as regular soldiers on a wider scale (i.e. in whole Black Regiments) and the various reasons why the Confederacy refused to do so....on a large scale -- meaning instead of just individuals among whole regiments of regular Confederate units.

|

| 4th Tennessee Cavalry CSA, Black Trooper, Chickamauga, Sep. 1863. Artwork by Don Troiani Pg. 208, "Regiment's & Uniforms of the Civil War." |

One of the best documented examples occurred in September 1863, during the Battle of Chickamauga.

The 4th Tennessee Cavalry had a black servant named Daniel McLemore, servant to the Colonel of the regiment, organize a group of servants into a company of between 40-50 men. They were at first ordered to guard the horses of the soldiers, but sitting out of the fighting long enough, they asked a Captain Joseph P. Briggs, the company's quartermaster, if they could participate in the fighting.

Captain Briggs recalled that: "After trying to dissuade them from this, I gave in and led them up to the line of battle in which was just preparing to assault Gen. Thomas's position. Thinking they would be of service in caring for the wounded, I held them close up the line, but when the advance was ordered the negro company became enthused as well as their masters, and filled a portion of the line of advance as well as any company of the regiment. While they had no guidon or muster roll, the burial after the battle of four of their number and the care of seven wounded at the hospital, told the tale of how well they fought."

|

| Muster roll and gravestone of Confederate cavalryman Wiley Stewart, Co. H, 4th Tennessee Cavalry CSA. Both list him as a Free Man Of Color. Stewart is buried among comrades at the Confederate cemetery in Griffin, Georgia. |

One more interesting note about the service of these Confederates of Color that Deniers of their service rarely mention is their status as seen by the Union military when captured in the course of the war.

Black Confederates were often captured on the field and imprisoned in Union prisoner of war camps along with all of the Confederate servicemen -- pretty bizarre if these men were not viewed as enemy combatants in some capacity, huh?

Black Veterans In American Wars

Now allow me to add another critical point about African-Americans in the ranks of Southern citizen militias: they did not exist in a vacuum.

Prior to the American Civil War, individual black men -- both slaves and free men of color -- also served in the militias of Southern States during the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) preforming the same jobs as members of those State militias and military units as their grandchildren would later do in the War Between the States, including -- yep, you guessed it -- combat roles.

|

| At the final phase of the Battle of Cowpens (January 17, 1781), a young African American soldier and bugler named Asher Crockett, heroically rode up and fired his pistol at a British cavalryman saving the life of his commanding officer, Colonel William Washington. (Painting by William Ranney) |

During the final stages of the battle, Colonel Washington and several of his dragoons were involved in a personal duel with several British Legion Cavalry officers -- including the infamous Colonel Banastre Tarleton. As Washington was about to be cut down by a British saber, Crockett rode up and shot the man from his horse with a pistol, likely saving his commander's life.

Crockett was only one of an estimated 10 or 12 African-Americans present among the Continentals and local militia forces fighting at the battle. This is just one of many individual profiles of courage and personal valor shown by Black Southerners in over a hundred years of American wars prior to the War Between The States in 1861.

There are also many accounts coming to light in recent years about the service of Black British Loyalists who also fought with Loyalist militias and were formally enlisted among the British Provincials and Hessian ranks in the regular British Army as uniformed soldiers, among the other usual service jobs.

Of course, if we hold to the Black Confederate Denier argument of "slaves not soldiers" then none of these American men of color could be counted as real soldiers either -- just musicians, cooks, and "ditch diggers" brought there by some rich white officer against their will.

|

| The

Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA.) January 29, 1861. One of the earliest examples of a Southern free person of color offering to raise a military company. Note that Mr. Joe Clark was a military veteran, wounded in the "Indian War" (Likely the Creek War of 1836). |

Sorry, but as my grandpa would have put it, that dog just don't hunt. Simple common sense logic suggests this could not possibly be the case.

Curiously your average pointy-nosed Denier "intellectual" doesn't make any attempt to point out this contradiction beyond -- yep, you guessed it! -- again parroting and stonewalling the previous talking points.

How Many Black Confederates Were There?

Depending on who you listen to and what sources you site the number of Black Confederates who preformed the duty of soldier ranges from a few hundred to around 100,000 -- though neither one is completely accurate.

Now obviously the 100,000 number is an gross exaggeration, but the few hundred number is also in dispute.

Historians estimate that the aggregate for the size of the Confederate military during the four years of the war totaled between 750,000 - 800,000 soldiers, sailors and home guard (state militias). Of this number about 25% of these men were under the command of General Robert E. Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia, which reached it's peak strength of around 90,000 in June of 1862.

Now its possible that 100,000 Southern black men (again slaves and freemen alike) could have been in service in those roles over those four years collectively -- possible, though not very likely.

However, keep in mind that not every one of these African-American in Confederate service was necessarily a Southern loyalist by any stretch of the imagination -- again I site the story of Robert Smalls as the best example. Loyalty to masters, neighbors and friends is more of a common factor, and each level of loyalty different for every individual person.

Some of the slaves and "body servants" would leave and not come back after their master was killed and wounded, and almost certainly some took advantage of being close to Union lines to head North to Canada and freedom; while others would return and stay with their former master's units and continue to serve as they saw fit.

In fact, on occasions when Black Confederates were captured by Union soldiers and imprisoned in POW camps, many of them refused to turn coats, or abandon their fellow Confederates.

No, the true number would likely be in the 10,000 - 60,000 range for those Southern blacks who performed service roles in the Confederate army, but not so much the actual act of performing soldiers' work, or taking part in battle. The actual number who might have served on the battlefield over four years collectively might be best estimated at 5,000 at the most.

This estimate is largely shared by several historians including Professor John Stauffer, the former chair of American studies at Harvard University in a well-written 2015 article entitled: Yes, There Were Black Confederates. Here's Why when he states:

"I estimate that between 3,000 and 6,000 served as Confederate soldiers. Another 100,000 or so blacks, mostly slaves, supported the Confederacy as laborers, servants and teamsters. They built roads, batteries and fortifications; manned munitions factories -- essentially did the Confederacy’s dirty work."

Also keep in mind that, with a couple of exceptions (the escorts who rode with General Forrest's cavalry, or the 30-40 man group of Black Confederates of the 4th Tennessee Cavalry who took part together in a couple of fights mentioned previously) there were no whole regiments, or large units of Black Confederates as soldiers until just before the close of the War itself.

|

| A more accurate depiction of the service of a Black Confederate showing an individual integrated into the ranks of a Southern unit, as opposed to the larger numbers in whole segregated regiments as the United States Colored Troops were. Artwork by artist Bradley Schmehl. |

Now consider the size of actual Civil War regiments during the course of the war itself. Each regiment had about ten companies that consisted of about 80 to 100 men, giving us a regimental strength of anywhere between 800 to 1,000 men. There was an estimated 1,010 Confederate regiments throughout the war.

Its believed that each Confederate regiment had no less than about 4 to 10 black slaves or men of color at any given time throughout the war. So on average one can estimate that the number of African-Americans in these ranks comes to anywhere between 4,000 to just under 10,000 -- the latter being the most liberal estimate.

However, it should be pointed out these are not consistent numbers, and certainly not all of these estimated men were Black Confederate loyalists.

Ultimately we will likely never know the true number since their service was largely only recognized by the men they served with, and most official records often didn't list every single act of heroism that "official" soldiers preformed, let alone what a black drummer boy, or wagoner, or cook who picked up a fallen rifle and joined the battle line would have done.

At best, in each of those regiments, out of the possible 4 to 10 black men, then number that actually saw real combat would be about one or two at best out of a regiment of hundreds. An overall moderate average of around 2,000 or so overall in an army estimated at about 800,000 men.

Now when compared to the larger number of African-Americans loyal to the Union, and who served with distinction as members of the USCT (approximately 178,600 Union Army soldiers spread over about 160 full regiments of about a thousand men each -- of which an estimated 140,000 were themselves Southern born) in segregated all-black regiments, the numbers of Black Confederates are hardly impressive. These small number of Black Southern loyalists ultimately did nothing to turn the war in favor of the South.

Now here is where the Deniers get all discombobulated, and the rants come out: You're just trying to cover up what the war was REALLY about! It was all about slavery!

It should be pointed out that the presence of these Confederates of Color in the ranks of the Confederate soldier does nothing to prove, or disprove, one way or another what the causes of the war were. It does not chance what was written in the Ordinances of Secession for several Southern States. It does not change what Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens said in his infamous "Cornerstone Speech" or the provisions about slavery in the Confederate Constitution. Neither does it change the reality of the racial attitudes towards people of color in America in the 1860s.

Any so-called "neo-Confederates" who believe that the presence of these men and their service undermines the national historical narrative on the reasons for either secession and the war that followed simply delude themselves, and making that case is not a valid reason for respecting the service of these men, or any Confederate soldier no matter their ethnic origin.

Ultimately the existence of African-Americans as Confederate Veterans does not alter historical facts that even most Confederate heritage groups acknowledge to be true. The ever-present argument over the specific causes of the War Between the States won't be settled just because it can be proven that some of the boys who wore gray and butternut and took shots at invading blue-bellies had darker skin tones.

Whatever latent fears one has for recognizing these men for their service, or calling them soldiers -- even unofficial ones -- one thinks will impact civil war history, such recognition does nothing to prove or disprove the role of slavery in the conflict, nor discredit one side or the other. Nor is this the reason that Confederate heritage groups and other proud Confederate descendants choose to honor these men, or any other Confederate veteran.

Modern Acknowledgment Of Black Confederates

In truth, Black Confederate Denial historical negationism truly doesn't offer much more than a repeat of the same previous talking points, as if those points alone are the only relevant facts. Deniers believe that they and they alone have the moral imperative to interpret history properly.

That is not to say they still don't have a few more arguments left, even though the next cards in their wobbly house stand on very shaky foundations.

The next argument thrown out by Deniers is to claim that the argument over Black Confederates is about downplaying, or diminishing the role of the United States Colored Troops and their service to the Union for freedom.

This argument in particular is one of the most insulting, especially for people like this writer who hold nothing but the highest respect for all American soldiers and their service to the history of the country of my birth. I mean every one of them, including: Colonial militiamen, Continental Army Regulars, British Loyalist Provincials, Native-American braves, US military service persons who fought in all of America's foreign wars, and yes, especially Union and Confederate Veterans.

I have no personal issue with honoring the service of the Union soldier, even though he was admittedly the invader and killed my own Confederate great-great-grandfather at Chickamauga. I most certainly respect the Confederate soldier, and I am certainly proud to be the descendant of one. Certainly I will defend his good name -- the name I share -- by all honorable means and with as much common sense logic I can muster.

I also respect the memory of those Union men no less than I do the memory of the British soldiers who landed in America in 1776 to try and restore the authority of the British Crown to the newly independent and united thirteen sovereign American States. They were invaders, but also men who fought for principles they believed in, and individuals who had dreams and lives no different than the people they fought.

Also as someone who once helped with the cleaning of the graves of fallen USCT soldiers, this proud Confederate descendant would be one of the first to acknowledge the service and heroism of the men of the USCT and their role in the preservation of the Union, and putting an end of American slavery.

Now here is where a Black Confederate Denier would be choking on his drink, or otherwise getting his computer screen wet from spitting said drink on it. So you admit it?! The Confederates fought for slavery!

Yeah and this leads into one of the Denier's biggest and probably most repetitious talking points: the false claim that the honoring of Black Confederates by modern-day Confederate heritage defenders, is about deflecting the so-called "true cause" of the War Between the States and denigrates the honor of Black Union Veterans.

A Black Confederate Denier will drone on-and-on-and-on their claim that Confederate heritage defenders and groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy have only brought up the subject of Black Confederates in the years following the end of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Era. Some will even offer a specific year -- 1977.

It was in 1977 that the TV mini-series Roots, based on the extraordinary novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family by Alex Haley, played in millions of homes across America. The story depicts the terrible personal horrors of African slavery from the dramatized point of view of the linear descendants of Mr. Haley himself, starting with an African boy named Kunta Kinte, portrayed brilliantly by actor LeVar Burton of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Reading Rainbow fame.

Now here is where we start to delve into conspiracy theory territory folks. Please bear with me because this is where some of the more long-winded Deniers set up the rest of the deck onto their now wobbly house of cards.

The argument advanced by these Deniers, and other historical false flaggers who promote them, is that after the release of Roots and the end of the Civil Rights Movement, groups like the SCV and UDC began propping up Black Confederates in an effort to prevent what they saw as the beginning of the backlash and destruction of Confederate symbols at the time.

To solidify this absurd claim, Deniers site two reports from then SCV Commander-in-Chief Mr. Dean Boggs written in early 1977 as proof positive of their claims. The following are the excerpts of those memos, in their entirety:

From the Report of the Adjutant-in-Chief, Feb. 28, 1977:

1. THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF SAYS:

Commander-in-Chief Dean Boggs has requested that the following information be published.

To counteract the drive of NAACP to ban the display of the Confederate Flag, the playing of Dixie, etc. and to counteract such propaganda movies as “Roots,” I have persuaded Compatriot Francis W. Springer, a historian and talented Virginia writers to write a book on the contribution of Negroes in the south to the Confederate war effort.

He is going to research all sources available but feels sure the sources available to him will not tell the whole story by any means. Thus, I call your attention to the following request from Compatriot Springer for assistance from all Compatriots.

COMPATRIOTS! GET ON THIS PROJECT RIGHT AWAY. SEARCH YOUR FAMILY PAPERS FOR LETTERS AND DIARIES OF 1861-18 65; WRACK YOUR MEMORY FOR STORIES HANDED DOWN BY THE “OLD FOLKS”; VISIT YOUR LOCAL MUSEUMS AND LIBRARIES FOR RECORDS OF SERVICES PERFORMED BY SOUTHERN NEGROES, SLAVE OR FREE, FOR THE CONFEDERACY

Suddenly, after more than 100 years, it seems to have become “good politics” to assert that the flags, uniforms, and songs of the Confederacy are repugnant to negroes. This is childish nonsense. Politics often ignores the truth, and the truth is that the majority of Southern Negroes, slave and free, sided the Confederate war effort tremendously. Some were under arms and in combat.

From the Report of the Adjutant-in-Chief, April 30, 1977.

1. THE COMMANDER- IN-CHIEF SAYS:

Commander-in-chief Dean Boggs has requested that the following information be published:

CONTRIBUTIONS OF SOUTHERN NEGROES TO THE CONFEDERATE WAR EFFORT

All Compatriots are reminded of the announcement in the last issue of the General Headquarters News Bulletin that Compatriot Francis W. Springer, a talented writer and historian, has been persuaded by the Commander-in-chief to write a book on the above subject.

This is to counteract the efforts of the NAACP to portray the Confederate Flag and the playing of "Dixie", as offensive to blacks, and the propaganda line of such movies as "Roots," By their work on the farms, by accompanying their masters to War, and in many other ways, Southern Negroes made a valuable contribution to the Confederate war effort. After they were freed, many of them would not leave their former masters.

It is believed that the record will show that the majority of Southern Negroes made a greater contribution to the Confederacy, than the minority did for the Union.

Compatriot Springer is going to research all sources available to him but he is sure the sources available to him will not tell the whole story. He needs your help!

Please forward to him all items on this subject in your family history and records, and please research your local library and any other sources available to you.

*Source: Sons of Confederate Veterans National HQ.

So, do these particular statements offer proof positive of the Denier's claim that prior to 1977 and the premiere of Roots that there were no Black Confederate Veterans?

Not even close!

The truth there is a bit more reasonable that some imagined desperate meeting in a smoke-filled room, or some memos passed down from the heads of the SCV and UDC.

The real reason that more emphasis on Black Confederates came about in the 1970s has far more to do with the overall effort on the part of Americans to recognize black achievements in every part of American history that began about that time. Effort on the part of forward-thinking Americans which had more to do with countering the overall whitewashing of US history in academia at the time -- particularly American military history.

Prior to the early 1970s only a few academics and serious history buffs were even aware that Black Americans fought both as Patriots and Loyalists in the American Revolutionary War, or of the notable efforts of the Buffalo Soldiers in the American West and the Spanish-American War (1898), or the 369th US Infantry Regiment "Harlem Hellfighters" who fought with the American Expeditionary Forces in the First World War (1917-1918).

Indeed few Americans in the general public really even knew about the United States Colored Troops who fought for the Union Army until the 1989 release of the film Glory which depicted the somewhat accurate account (for Hollywood) of the early service of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first African-American units of the US Army.

Now the fact that few people had public knowledge of the service of any of these men does not mean they did not exist, or that the service they provided as soldiers and veterans counts for any less. Obviously someone remembered who they were and finally made the effort to move past the historical whitewashing of US history to tell their story. These men, long put into the background of history are finally getting the recognition they deserve for their valor and sacrifices -- many times in the face of hostile discrimination from the very country they fought to defend.

In truth Confederate heritage organizations and groups that honor the Confederate citizen soldier have always known about these Confederates of Color, and honored their individual service as Southern Veterans since the end of the War Between the States.

If anything the two memos sited show that the SCV was getting onboard with a larger national narrative that was shifting to include public awareness of the service of African-Americans. The fact that attacks on Confederate symbols by the NAACP and the broadcasting of the series Roots were the catalyst for launching a broader effort to make the public aware of this fact are irrelevant, and do not make a vast "neo-Confederate" conspiracy.

Some Deniers even go a bit farther and claim that there were no mention of Black Confederates as Confederate Veterans prior to the release of Roots in 1977.

Those claims are more than easy to refute.

The following are pictures from several reunions of the United Confederate Veterans, all of which include several Black Confederate Veterans present among the ranks.

|

| 1916 UCV Reunion, Birmingham, Alabama. |

|

| 1909 UCV Parade, Memphis, Tennessee. |

|

| 1931 UCV Reunion, Asheville, North Carolina |

|

| Richmond, Virginia at R.E. Lee Camp 1917. |

|

| 1929 UCV Reunion, Mufreesboro, Tennessee. |

|

| 191 UCV Reunion, Lancaster, South Carolina. |

The following newspaper accounts also show that Black Confederates were far from forgotten by their local communities, and acknowledged by their fellow Confederate Veterans for their service. Many of these Confederates of Color were buried with full honors -- and in Confederate uniform!

| |

| Richmond (Virginia) Dispatch, November 29, 1891. |

|

| Darlington, South Carolina, November 1907. |

|

| The Anderson (South Carolina) Intelligencer, March 18, 1886 |

Black Confederates were very much a part of the original United Confederate Veterans and were in fact honored as any other Confederate veteran was locally by their peers (white and black) all throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of those same Black Confederates were often buried in Confederate uniforms with battle flags draping their coffins and carried by white and black pallbearers who were also former war veterans.

Black Confederate Veterans attended many of the United Confederate Veterans reunions following the end of the War and well into the 1940s, something that modern-day social justice warriors will scream could not have been possible because of the Jim Crow segregation at the time.

Now the Black Confederate Denial house of cards begins to fall apart and your typical Denier starts to rave and shout that these men were acknowledged just to promote the old "faithful slaves" narrative.

But wait? Didn't these folks just claim that there were no Black Confederates honored prior of the end of the Civil Rights Movement? If so then why would the Confederate Veterans themselves and the organizations honoring their memories carry on honor these Confederates of Color?

Obviously the idea that these people actually respected and cared about these men as Confederate Veterans, let alone acknowledged their service as that of a typical Confederate soldier, is something far beyond the limited worldview of the Denier.

That respect was well reciprocated, as evidenced by the story of Black Mississippi Representative Mr. John F. Harris, a native of Greenville, Mississippi. A former slave and Black Confederate Veteran, he spoke eloquently in February of 1890 on his experiences serving with the Confederate Army at the battles of the Seven Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign around Richmond in 1862 in favor of the creation of the Jackson, Mississippi Confederate Soldiers Memorial that was later built a year later and stands on the state capitol.

Here the Deniers scream out with shrill voices: But there is no academic study of Black Confederates before the 1970s!

Once again, their narrative is very much in error.

In fact one of the earliest scholarly works that mention Black Confederates was historian Charles Harris Wesley's essay written in The Journal of Negro History (Volume IV -- July, 1919 -- No. 3, Pages 239-253). The fact this is not a journal usually read by Civil War historians in general meant that the essay went largely unnoticed, I will give the Deniers the benefit of the doubt. Mr. Wesley, who was both African-American and former member of the NAACP, certainly cannot be called a "neo-Confederate" (sic) by any stretch of the imagination.

Wesley began by noting that in the early days of the War most black Southerners saw the Union invasion of the South as an attack on independent States and their homes, same as white Southerners (and other people of color in the Confederacy, though Wesley overlooked this detail at the time). He then traced the Confederacy's use of black labor on defense projects and wrote a state-by-state examination of the policies of each State toward the role of Black Southerners in the war, noting that many of the Southern States allowed black enlistment into local militia and home guard ranks.

Because of its general nature, Wesley's essay does not mention any particular individual service, and concludes (erroneously as it has been demonstrated) that these men likely didn't serve in any major battle. The essay also traced the wide debate with the Confederate Congress over the idea of creating whole regiments of Southern slaves formally into Confederate Soldiers -- a history this blogger concedes to be what the national historical record concludes to be accurate, and has never denied in this post.

None-the-less the fact this essay was written well before the 1970s when Deniers claim a conspiracy was established to rewrite the historical narrative and create a fictitious "Rainbow Confederacy" shows that either Black Confederate Deniers omit facts that discredit their own narrative, or they simply do not do their homework very well.

Honoring The Black Confederate Veteran